Please enjoy the free portion of this monthly newsletter with our compliments. To get full access, you might want to consider an upgrade to paid for as little as $15/month. As an added bonus, paid subscribers also receive our weekly ALPHA INSIGHTS: Idea Generator Lab publication, which provides updated market analysis and details our top actionable trade idea very Wednesday, as well as other perks, including periodic ALPHA INSIGHTS: Interim Bulletin reports and exclusive video content.

Executive Summary

Democracy in America

Economic Overview: Beggars Banquet

Geopolitical Perspectives: Steel Wheels

Market Analysis & Outlook: Flashpoint

Conclusions & Positioning: Aftermath

Democracy in America

Alexis de Tocqueville was a 19th century French aristocrat and diplomat known for his philosophical writings on sociology, political science, and history. He is probably best known for his two volume magnum opus, Democracy in America, published following extensive travels throughout the United States during a diplomatic mission in 1831. Observing from the perspective of a detached social scientist, Tocqueville described the United States during a period when market revolution, Western expansion, and Jacksonian democracy were radically transforming the fabric of American life.

As Tocqueville came to understand it, this rapidly democratizing society had a population devoted to “middling” values, which wanted to amass vast fortunes through hard work. In Tocqueville’s mind, this explained why the United States was so different from Europe. In Europe, he claimed, nobody cared about making money. The lower classes had no hope of gaining more than minimal wealth while the upper classes found it crass, vulgar, and unbecoming of their sort to care about something as unseemly as money. With many virtually guaranteed wealth, they took it for granted. At the same time in the United States, workers would see people fashioned in exquisite attire and merely proclaim that through hard work they too would soon possess the fortune necessary to enjoy such luxuries.

However, Tocqueville warned that modern democracy may also be adept at inventing new forms of tyranny because radical equality could lead to the materialism of an expanding bourgeoisie and to the selfishness of individualism. Tocqueville worried that if despotism were to take root in a modern democracy, it could see “a multitude of men, uniformly alike, equal, constantly circling for petty pleasures, unaware of fellow citizens and subject to the will of a powerful state which exerted an immense protective power.” He compared a potentially despotic democratic government to a protective parent who wants to keep its citizens as “perpetual children” and which does not break men’s wills, but rather presides over people in the same way as a shepherd looking after a “flock of timid animals.”

In a chapter entitled, The Road to Servitude, Tocqueville expressed his ardent support of liberty, writing:

“I have a passionate love for liberty, law, and respect for rights. I am neither of the revolutionary party nor of the conservative. Liberty is my foremost passion…But one also finds in the human heart a depraved taste for equality, which impels the weak to want to bring the strong down to their level, and which reduces men to preferring equality in servitude to inequality in freedom.”

Some 80 year later, it was this very concept that caught the attention of a brilliant student at the University of Vienna by the name of Friedrich Hayek, who was studying economics there following his service during WWI. Hayek, who demonstrated exceptional understanding of Austrian economist Carl Menger’s work, was hired right out of University by Ludwig von Mises, who encouraged him to expand upon Tocqueville’s ideas within the Austrian economic discipline. With the help of Mises, Hayek founded and served as the director of the Austrian Institute for Business Cycle Research for nearly 10 years, before joining the faculty at the London School of Economics in 1931. There he was quickly recognized as one of the leading economic theorists in the world.

In 1932, Hayek engaged in correspondence with John Maynard Keynes through a series of open letters that were published in the The Times. Therein, he famously argued in favor of private investment as the superior path toward economic recovery in Britain over government spending programs as argued for by Keynes. Hayek’s embrace of free market capitalism over the command and control theories popularized by Keynes was the cornerstone of his work in economics. Some have speculated that Hayek may have felt a need to respond to the success of Keynes, General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. But, it was his concern over the general view in Britain’s academic circles — that fascism was a capitalist reaction to socialism — that actually motivated him to write the book, which eventually came to be titled, The Road to Serfdom — a tip of the hat to Tocqueville.

Therein, Hayek argues that Western democracies, including the United Kingdom and the United States, have “progressively abandoned ‘that freedom in economic affairs’ without which personal and political freedom has never existed in the past.” He goes on further to imply that society has mistakenly tried to ensure continuing prosperity by centralized planning, which inevitably leads to totalitarianism:

“We have in effect undertaken to dispense with the forces which produced unforeseen results, and to replace the impersonal and anonymous mechanism of the market by collective and ‘conscious’ direction of all social forces to deliberately chosen goals.”

Hayek, like Tocqueville before him, was convinced that socialism, while presented as a means of assuring equality, does so through “restraint and servitude,” while “democracy seeks equality in liberty.” Hayek further argues that planning, because it is coercive, is an inferior method of regulation, while the competition of a free market is superior “because it is the only method by which our activities can be adjusted to each other without the coercive or arbitrary intervention of authority.”

Centralized planning was seen as inherently undemocratic in Hayek’s view, because it requires “that the will of a small minority be imposed upon the people.” The power of these minorities to act by taking money or property in pursuit of centralized goals, destroys the Rule of Law and individual freedoms. Where there is centralized planning, “the individual would more than ever become a mere means, to be used by the authority in the service of such abstractions as the ‘social welfare’ or the ‘good of the community.’” Even the very poor have more personal freedom in an open society than a centrally planned one. “While the last resort of a competitive economy is the bailiff, the ultimate sanction of a planned economy is the hangman.” Hayek saw socialism as a hypocritical system because its professed humanitarian goals can only be put into practice by brutal methods “of which most socialists disapprove.” Such centralized systems also require effective propaganda, so that the people come to believe that the state’s goals are their own.

Although Hayek believed that government intervention in markets would lead to a loss of freedom, he recognized a limited role for government to perform tasks for which he believed free markets were not capable:

While Hayek is opposed to regulations that restrict the freedom to enter into trade, or to buy and sell at any price, or to control quantities, he acknowledges the utility of regulations that restrict legal methods of production, so long as these are applied equally to everyone and not used as an indirect way of controlling prices or quantities, and without forgetting the cost of such restrictions.

He notes that there are certain areas, such as the environment, where activities that cause damage to third parties — known to economists as “negative externalities” — cannot effectively be regulated solely by the marketplace. The government also has a role in preventing fraud, and in creating a safety net.

He concludes: “In no system that could be rationally defended would the state just do nothing.”

In 1974, Hayek was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his theory of price discovery — how price changes relay information that helps people determine their own economic plan. In 2007, the University of Chicago Press estimated that more than 350,000 copies of The Road to Serfdom have been sold. It was placed fourth on the list of the 100 best non-fiction books of the 20th century. Milton Friedman described it as “one of the great books of our time.”

Fast forward to the 21st century. Over the past 50 years, the state has done much more than do nothing. Indeed, the intervention of Federal Reserve alone has contributed mightily to both the successes and failures within the U.S. economic landscape. The 1977 amendment to the Federal Reserve Act expanded the Fed’s prior statutory mandate of “stable prices,” to a dual mandate, which now includes the promotion of “maximum employment.” This change set into motion a complex balancing act driven by changes in monetary policy designed to “optimally price” the cost of money. The problem with this system, as Hayek predicted, is that it gives the government the power to arbitrarily choose the winners and losers. Why should poorly run businesses not be allowed to fail? Would it not allow those businesses to be restructured and recapitalized by more prudent management and investors?

But, it’s not just the principle of the matter — it’s the process. The tools and methods at the Fed’s disposal to adjust policy — the overnight funds rate and open market operations — are blunt instruments, and the models that dictate the timing and magnitude of policy changes are too subjective. They are, in fact, based upon the biased interpretation of lagging and notoriously unreliable data by a board of unelected governors, whose motivations have been unsurprisingly influenced by ego, career ambition, and arguably even politics — despite being a non-partisan Federal agency.

Moreover, since at least 1999 — with few exceptions — the FOMC has done little more than follow the market yield on the 2-year U.S. Treasury note with a delayed reaction. More often than not, the Fed’s indecision, or lack of responsiveness to the market, has resulted in undesirable economic consequences — most notably in 2000-01 ahead of the Tech Wreck, in 2007-08 ahead of the Great Financial Crisis (GCF), and lest we forget, in 2022-23 following the COVID-19 pandemic inflation. Jeffrey Gundlach, the “New Bond King” — as Barron’s once dubbed him, has argued for years that the FOMC should be abolished in favor of a systematic approach to interest rate management that targets the 2-year Treasury yield. Gundlach is probably right. Based upon the 2-Year Treasury yield, the market has a better historical track record when it comes to correctly timing directional changes to monetary policy than the FOMC.

But is the Fed following the market, or is the market anticipating future Fed policy action based upon inferences derived from the comments of Fed governors. Prior to the GFC, the Fed used to pride itself on its secrecy. It was rare to hear anything novel come from the mouth of a regional Fed governor. Fed watchers were relegated to gauging the potential for a policy change by observing how full former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan’s briefcase appeared as he walked across the street to an FOMC meeting. Greenspan’s post-meeting pressers and congressional hearings were chock-full of cryptic language that kept economists and media pundits guessing for days what he actually meant. Conversely, today’s Federal Reserve claims to embrace transparency. But from our perch, it appears that the Fed is now most concerned with how its next policy action might be judged by history, thus elevating its own self-importance above that of the nation it is supposed to serve.

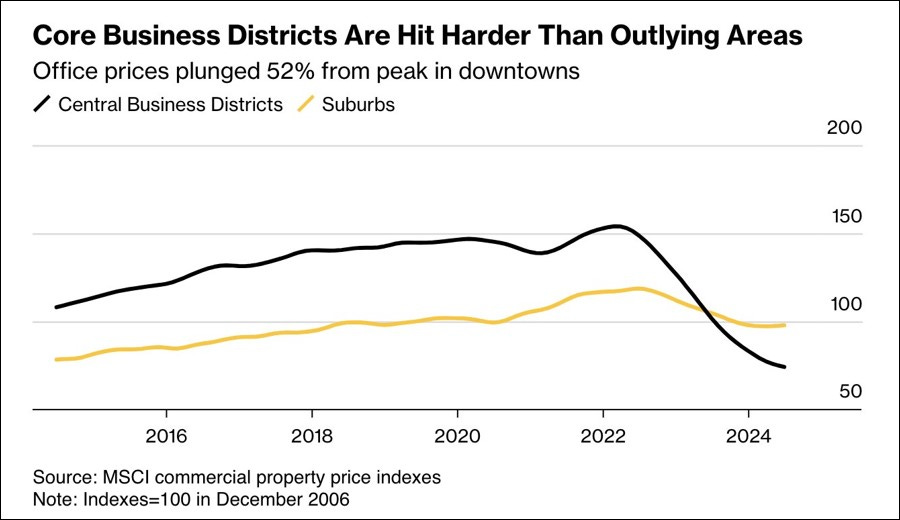

Indeed, the Fed’s actions do have consequences. There are winners and losers. For example, zero-interest-rate-policy (ZIRP) resulted in a near decade-long period of financial repression, which forced retirees and savers to either take risks that were inappropriate for their personal circumstances, or forgo earning a return on their money, while the federal government ran up the national debt. At the same time, low mortgage rates incentivised commercial property investors to overpay by a factor of two-fold for downtown office properties, while inciting 30-40% of homeowners to overextend themselves on houses that they can not afford to maintain. As evidenced by the fact that media pundits and market participants alike are now hanging on every word that comes out of a Fed Governor’s mouth (Fed officials are now averaging three or more speaking engagements per week), the market’s current obsession with monetary policy appears to be warranted. Like the road to hell, the road to serfdom is also paved with good intentions.

Economic Overview: Beggars Banquet

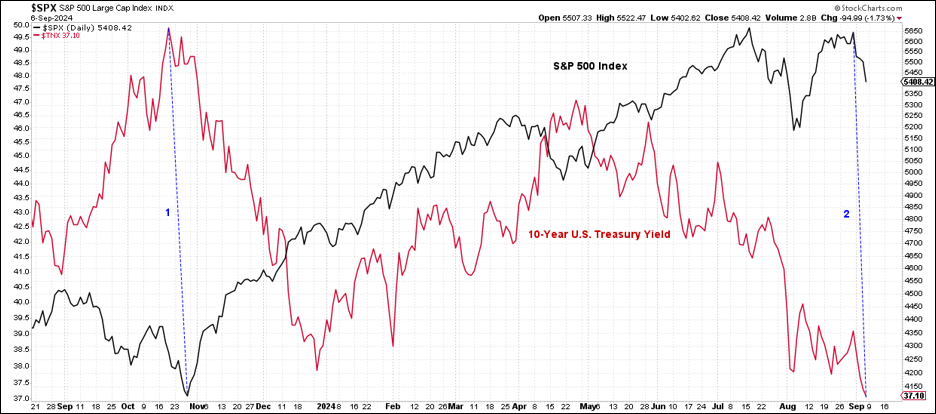

In November 2023, the market began speculating that the Fed was poised to begin a rate cutting cycle. Numerous hints were dropped by various Fed speakers — including the Fed Chairman himself — that the Fed was done hiking rates. The equity markets cheered, and a consensus view began to congeal around the so-called soft-landing narrative, or in some circles — a no-landing narrative. By December of last year, Fed funds futures were pricing in as many as seven quarter-point rate cuts in 2024. The S&P 500 rallied to SPX 5250 by the end of the first quarter, despite the fact that 10-year Treasury yields had backed-up some 90 bps. Shortly thereafter, following a few sequentially hot inflation prints, the market realized that the Fed may have just been telling them what they wanted to hear — or “jawboning the market,” as it has come to be known — following the August-October rout last year. The benchmark index dropped a quick 6% over three weeks in April.

Since that time, the inflation data has cooled, pushing the soft-landing narrative back to the fore until mid-July. Then something else happened. The unemployment data began to soften. The July Non-Farm Payroll (NFP) report came in well below expectations, pushing the unemployment rate up to 4.3%, thus triggering the Sahm Rule. For the unindoctrinated, Economist Claudia Sahm, formerly of the Federal Reserve and the Council of Economic Advisors, developed a heuristic indicator for determining when an economy has entered recession now known as the “Sahm Rule.” The indicator signals the start of a recession when the 3-month moving average of the national unemployment rate (U-3) rises by 0.50 percentage points or more above its 12-month low. The Sahm Rule has triggered approximately 1-3 months into the last several recessions with the beginning of each recession retroactively determined by the NBER. The model has been praised for its simplicity and historically low rate of false positives. The current reading is 0.57 percentage points, up from a 12-month low of 0.13 percentage points. As such, the probability is increasingly high that the U.S. entered recession during the month of July, if not earlier.

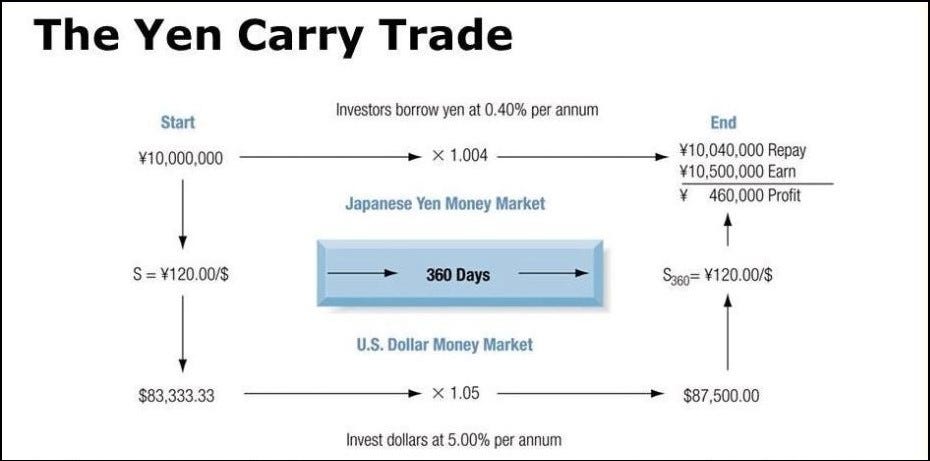

Concomitant with a softening economic backdrop, the Nasdaq 100 and the S&P 500 peaked on July 10th and July 16th, respectively. The benchmark index again dropped a quick 5% over the subsequent 10 days, but recovered about half of the decline as traders rallied the market into month-end July. Then, during the overnight session on July 31st, the Bank of Japan announced an unexpected rate hike, thus boosting its policy rate to 25 bps. While that may not seem like a lot, as a percent of the BoJ’s then prior policy rate of 0-0.1%, it effectively quintupled cost of overnight money to financial institutions without warning. Stocks began to drift lower over the next two days as hedge funds unwound some of their riskier bets going into the weekend. The following Sunday saw the Nikkei plunge by more than 12% overnight — its worst single-day decline since the 1987 stock market crash — as the Japanese Yen rose 14.3% over the prior three days.

On Monday, August 5th, U.S. investors awoke to a pre-market surge in volatility that spiked the VIX to 65% initially, leading equities to gap down on the opening bell. They hit their intraday lows in the first hour of trading. After all of the dust settled the S&P 500 had experienced a 9.7% peak-to-trough decline, while the Nasdaq 100 fell nearly 16% before arresting its decline. The VIX settled in to close the day at around 38.5%, but has since retrenched to as low as 15% by month-end August. Media reports quickly jumped on what must have appeared to them to be a novel angle — the “unwinding of the Yen carry-trade.”

But as long-time readers will know, we first highlighted the Yen carry-trade as a key risk to capital market stability last September in Issue #25. We again discussed it last month in Issue #36. And as subscribers to our more comprehensive ALPHA INSIGHTS investment strategy & trading advisory service will know, in the August 1st issue of the monthly Review & Outlook, we upgraded our technical rating on the JPYUSD cross from Bearish to Neutral, following the BoJ’s rate hike on July 31st. Without belaboring the point, we would simply mention that this is not the first time that we’ve witnessed an outsized spike in the Yen. Indeed, the Yen jumped 19.8% over three months in late-2022. What is different today, is the technical damage that was done — the penetration above a 3-year descending trendline opens the door to a further rally to the late-2022 high, and then a structural downtrend line that’s been in place since 2021. The further the Yen rallies, the greater the pressure to unwind the Yen-carry trade.

How big is the Yen carry-trade? The answer is that nobody really knows for certain. Estimates range from as low as $500 billion according to UBS Japan macro strategist James Malcolm, to $1.1 trillion according to economists at London based TS Lombard, to as high as $20 trillion according to George Saravelos, Head of FX Research at Deutsche Bank. According to Malcolm, an estimated $200 billion has been unwound so far over the past several weeks — suggesting that there is still a high potential for further deleveraging related to the Yen carry-trade in the future.

If the compression of the yield spread between the cost of funds in Japan and the risk free rate in the U.S. — driven by a 25 bps hike by the BoJ — was the catalyst for a $200 billion unwind in the Yen carry-trade, then its worth asking the question: how will a 25 bps cut by the Fed not exacerbate the situation further? Moreover, how will the 250 bps of Fed rate cuts currently priced into the Fed funds futures curve not lead to a much more dramatic unwinding of the Yen carry-trade? Perhaps more importantly, what if it does? If the Fed’s playbook is to cut rates ever more aggressively in order to stimulate liquidity during a crisis, wouldn’t doing so during a massive unwinding of the Yen carry-trade just force more margin calls and accelerate the deleveraging? At least their actions would be well-intentioned.

Adding to the market’s anxiety, on August 21st, the BLS revised down their estimate of total U.S. job growth for the 12-month period ended March 2024 by -818K jobs. The events of the past month sent numerous Fed governors back to the propaganda podium in an effort to calm the market’s nerves. Indeed, even Claudia Sahm (the “Mockingjay” herself) has been paraded around various financial news media outlets in order to assist the Fed’s propaganda efforts, stating that “the economy does not look like it’s in recession”, contradicting recession concerns that she raised only a few months before.

On Friday, September 6th, the BLS reported that Non-Farm Payrolls grew by a lower-than-expected 142K in August. The street was looking for 162K new jobs during the month. The BLS also cut their estimate of July’s total new jobs by 25K to 89K, and their June estimate was revised down by 61K to 118K. The good news was that the BLS estimates that the labor force expanded in August by 120K, which pushed the U-3 unemployment rate down by 0.1 percentage point in August to 4.2%. However, the U-6 unemployment rate, which includes discouraged workers and those holding part-time jobs for economic reasons edged up to 7.9%, its highest reading since October 2021.

The market is currently positioning for a 25 bps cut to the Fed funds rate on September 18th. Both the weakening jobs data and the cooling inflation data support an easier monetary policy bias. If the Fed fails to deliver on a cut in September, then the market will throw a tantrum because Fed Chairman Powell has all but promised a cut in September. If the Fed delivers on a 25 bps cut, then we suspect the market will probably still throw a tantrum because it didn’t cut by 50 bps. And if the Fed delivers a 50 bps cut, we think the market will panic because it will finally realize that the Fed is worried that they’ve fallen behind the curve. From our lens, if the 2-year U.S. Treasury yield is correct, then the Fed is already around 173 bps behind the curve.

Geopolitical Perspectives: Steel Wheels

The United States of America faces the potential threat of a five front war. Along with