Please enjoy the free portion of this monthly newsletter with our compliments. To get full access, you might want to consider an upgrade to paid for as little as $15/month. As an added bonus, paid subscribers also receive our weekly ALPHA INSIGHTS: Idea Generator Lab publication, which provides updated market analysis and details our top actionable trade idea very Wednesday, as well as other perks, including periodic ALPHA INSIGHTS: Interim Bulletin reports and exclusive video content.

This month marks the 3-year anniversary of HUGE INSIGHTS: The Big Picture. As such, we wanted to begin this issue by extending our gratitude to all of our loyal subscribers for helping to make this newsletter a success. Thank you for your support!

Executive Summary

Understanding the Kondratieff Cycle

Economic Overview: Recession Watch - No Quarter

Election Inflection: Kamalot vs. Project 2025

Market Analysis & Outlook: Good Times Bad Times

Conclusions & Positioning: The Song Remains the Same

Understanding the Kondratieff Cycle

The so-called “Kondratieff Wave” hypothesizes that the global economy operates within the boundaries of a long-term, boom-bust cycle, whose typical duration can range between forty and sixty years. Its namesake is attributable to the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter, who studied the long-term cycle analysis of Nikolai Kondratiev with great interest and was sufficiently impressed with his conclusions such that in 1939, he proposed to name the cycle in his honor.

During the early 1920s, the Soviet economist Nikolai Kondratiev began studying economic cycles. After establishing himself as a leader in the field of academic research, Kondratiev (more popularly spelled Kondratieff), became the founder and first director of the Institute of Conjecture, in Moscow, whose original purpose was to engage in the study and analysis of world economic trends in order to develop a better understanding of agricultural economics with respect to the problem of food supplies. But the institute expanded to over 50 researchers in order to study all aspects of the global economy after it was commissioned by the Soviet government to provide proof that capitalist economies were subject to spontaneous and recurrent depressions and recoveries, and that another depression was imminent.

Following an exhaustive analysis of the prices of raw materials, finished goods, interest rates, foreign trade, wages, and bank deposits within the United States, British, German, and French economies, Kondratiev published his first writing on long-term cycles entitled, The World Economy and its Conjectures During and After the War. His analysis did agree with the prevailing Soviet political view that capitalist economies were indeed subject to spontaneous and recurrent depressions and recoveries, however, based upon his team’s research, he concluded that the boom-bust cycle was much longer than previously assumed, and that it did not appear poised to reach its peak until the end of the decade. The study inspired Kondratiev to further investigate the notion of a 50-year business cycle, the existence of which was first proposed by the Dutch economist Jacob Van Gelderen in 1913.

Kondratiev travelled abroad extensively over the next year, visiting universities in England, Germany, Canada, and the United States, to present and debate his conclusions. In 1924, Kondratiev published his completed theory of long-term business cycles in a paper entitled, On the Notion of Economic Statistics, Dynamics, and Fluctuations. In that paper, he laid out five key conclusions: First, that prosperity years were most common in the capitalist economies during upswing periods. Next, that agriculture suffered more frequent and longer depressions than did industry during price downswings. Additionally, that major technological innovations were conceived of in downswing periods, but were developed in upswing periods. Next, and importantly, that the gold supply increased and new markets were opened at the beginning of an upswing. And, finally, that the most extensive and devastating wars tended to occur during periods of an upswing.

The following year, his paper was expanded into a book published with the title, The Major Economic Cycles. Kondratiev’s economic cycle theory held that there were long cycles of about fifty years — give or take a decade. At the beginning of each cycle economies produce high-cost capital goods and infrastructure investments creating new employment and income, and demand for consumer goods. However, after a few decades the expected return on investment fell below the cost of capital leading to a sharp curtailment of investment. Eventually, overcapacity in capital goods would give rise to massive layoffs, reducing the demand for consumer goods. Unemployment and economic crisis ensue as economies contract. People and companies conserve their resources until confidence begins to return and there is an upswing into a new capital formation period, usually characterized by large scale investment in new technologies.

Influenced by his travels overseas, Kondratiev proposed that the Soviet government adopt a market-led industrialization strategy emphasizing the export of agricultural produce to pay for industrialization — along the lines of the Ricardian economic theory of comparative advantage. However, following the death of Lenin in 1924, Joseph Stalin, who favored complete government control of the economy, took over the reigns of the Communist Party and Kondratiev’s influence quickly waned. In 1927, Kondratiev was imprisoned for his pro-capitalist views, where he remained until his execution in 1938.

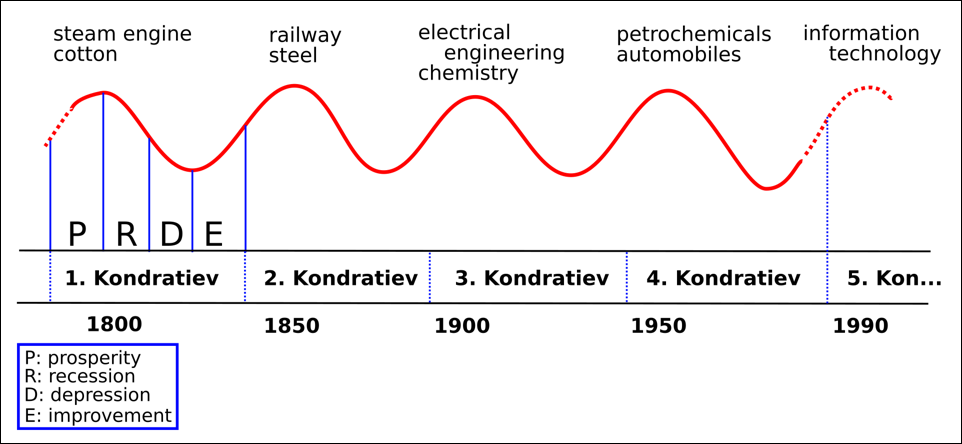

The graphic above illustrates an idealized view of the Kondratieff cycle dating back to the year 1800. While there have been many attempts to find a precise mathematical methodology to calculate the specific peaks and troughs of each Kondratieff wave in the long-term macroeconomic cycle, none of the modifications to Kondratiev’s original theory have yielded a concrete solution. The graphic above, which appears to have been created around the peak of the Dot-Com bubble, has been data-fitted so that the sine wave indicates a 50-year cycle slated to top around the year 2000, and divides each Kondratieff wave into four phases defined as prosperity, recession, depression, and improvement. Kondratiev himself identified three phases in the cycle, which he dubbed: expansion, stagnation, and recession. But, perhaps the most constructive new approach has focused on advancements in science and technology as means to mark past and future turning points.

A 2003 book by Charlota Perez entitled, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Bubbles and Dynamics of Golden Ages, also proposes that Kondratieff waves can be broken into four basic phases. Perez not only studied the work of Kondratiev, but also that of Schumpeter, who introduced innovation drivers into Kondratiev’s original framework. Schumpeter posited that Kondratieff waves were driven by radical innovations and forces of creative destruction. Perez says that each cycle starts with an irruption phase, where the innovations are already backed by financial capital and “are showing their future potential and making powerful inroads in a world still basically shaped by the previous paradigm.” Perez calls the second phase the frenzy phase. During that period, financial capital drives the buildup of the new innovation. Then a “turning point” begins, which is characterized by a collapse of the financial bubble followed by a deep recession. The third period she calls the synergy phase, where the conditions change in favor of a new innovation or paradigm. The final phase is called the maturity phase, and it occurs when the basic innovation of this wave begins to stagnate. Some have likened these four phases to the four seasons of the year. The first period being like a new Spring (boom), the second is like Summer — but always too short (expansion), the third period comes as Autumn does — baring the trees (stagnation), followed by a seemingly endless Winter to finally complete the cycle. Schumpeter described the final phase of the Kondratieff cycle this way:

“The economy falls into the throws of a debilitating depression that tears the social fabric of civilization, as the gulf between the dwindling number of “haves” and have-nots” increases dramatically.”

According to Perez, the turning point of the current or fifth Kondratieff wave was in 2001 when the Dot-Com bubble burst, and thus the synergy phase coincided with the period leading up to the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) and its aftermath. Normally, the maturity phase lasts around 10-20 years. Therefore, Perez assumes that the fifth wave will end between 2025 and 2030 — but it could take longer. Today, Perez is looked upon as one of the most important Kondratieff cycle experts, and her model, which identifies the different phases during each wave is considered to be the best explanation of the timing and the characteristics of the Kondratieff cycle. Perez’s model is illustrated in the table below. It’s noteworthy that some periods like the maturity phase in the third wave and the irruption phase in the fourth wave are overlapping. Another example that shows overlap is the maturity phase in the fourth wave and the irruption phase in the fifth wave.

The consensus view on Wall Street today has dubbed generative artificial intelligence (Gen-AI) as the primary subject of a new age of technological innovation. As such, under Perez’s model, one might be inclined to consider Gen-AI to be a prime example of the irruption phase of a new Kondratieff wave. But the same might have been said of the metaverse if we were having this discussion in October 2021, when Mark Zuckerberg famously changed the name of his company from Facebook to Meta Platforms. Then, META’s stock had just posted a new all-time record high of $384 in the month prior to the announcement. Zuckerberg acquired Oculus in 2014 for $2 billion, and had been quietly pouring money into the development of his metaverse concept. Investors gave the boy genius a long leash as the traditional ad-based business was thriving, but then investors began to do the math. Like the cartoon above suggests, “it’s the math that gets you.” And finally, a moment of clarity — the sudden realization that pouring billions of dollars into R&D year after year had not yielded any tangible results, and that increasing the burn rate was unlikely to change that fact. The stock plunged by 76% over the subsequent 12 months.

Today, the hyperscalers’ fascination with Chat-GPT seems more a kin to Zuckerberg’s fascination with the metaverse than it does to the massive worldwide infrastructure buildout of the internet back in the late-1990s. On June 25th, Goldman Sachs published a 31-page report entitled, Gen AI: Too Much Spend, Too Little Benefit?, led by Head of Global Research, Jim Covello, which details the firm’s concerns over the lack of a financial payoff from Gen-AI investments.

“My main concern is that the substantial cost to develop and run AI technology means that AI applications must solve extremely complex and important problems for enterprises to earn an appropriate return on investment (ROI),” said Covello. “We estimate that the AI infrastructure buildout will cost over $1 trillion in the next several years alone, which includes spending on data centers, utilities, and applications. So, the crucial question is: What $1 trillion problem will AI solve? Replacing low wage jobs with tremendously costly technology is basically the polar opposite of the prior technology transitions I’ve witnessed in my thirty years of closely following the tech industry.”

On July 29th, during a fireside chat at SIGGRAPH 2024 — the annual conference of the Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques — NVIDIA founder and CEO Jensen Huang and Meta founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg discussed the “transformative” potential of open source AI and AI assistants. Zuckerberg kicked-off the discussion by announcing the launch of AI Studio, a new platform that allows users to create, share, and discover AI characters, making AI more accessible to millions of creators and small businesses. Zuckerberg expounded that the advancements promise more tools to foster engagement, create compelling and personalized content — such as digital avatars, and build virtual worlds. “Every single website will probably, in the future, have these AIs,” Huang chimed in. Zuckerberg went on to say more broadly, that the advancement of AI across a broad ecosystem promises to supercharge human productivity, for example, by giving every human on earth a digital assistant — or assistants — allowing people to live richer lives that they can interact with quickly and fluidly. Seriously?! This is the problem that they are trying to solve — to create tools that allow Instagram influencers like Kylie Jenner and Kim Kardashian more personal time to enjoy life by creating a virtual assistant / cartoon version of themselves to answer their fan mail for them? At $2,386,000 per branded post, we’re guessing that influencers can afford their own personal assistants.

After hearing Huang and Zuckerberg’s conversation — again, using the Perez framework — with knowledge of the metaverse fiasco described above and the added ROI insight from Goldman Sachs, one might now conclude that rather than the dawn of a new era, we have instead entered the maturity phase of the fifth Kondratieff wave. Perhaps there is another overlap with a budding sixth wave of innovation, but with the S&P 500 index near its all-time record highs, its difficult to argue that we’re at the beginning of a new Kondratieff cycle. More likely, we are well-past the peak of the 5th wave as Perez’s model suggests — late-Autumn at best. While we still hold out the possibility that Gen-AI will lead to something meaningful over the next two decades, the path to get there could prove to be much longer and more arduous than the bullish consensus has the patience for. In the words of Lord Eddard Stark, “Winter is Coming!”

Economic Overview: Recession Watch, No Quarter

From time to time we’ve presented our economic dashboard, which includes five models that monitor various measures of liquidity, bank credit, employment, leading indicators, and yield curves, in order to determine the health of the economy. While four of our models have been signaling recession warnings over much of the past 24 months, one has remained decidedly neutral throughout that period — until yesterday.