Please enjoy the free portion of this monthly newsletter with our compliments. To get full access, you might want to consider an upgrade to paid for as little as $12.50/month. As an added bonus, paid subscribers also receive our weekly ALPHA INSIGHTS: Idea Generator Lab publication, which details our top actionable trade idea and provides updated market analysis every Wednesday, as well as other random perks, including periodic ALPHA INSIGHTS: Interim Bulletin reports and quarterly video content.

Executive Summary

The Economy: Continental Drift, Recession, and the Bear Steepener

The China Syndrome: On the Precipice of a Shadow Banking Crisis

Geopolitical Perspectives: Implications of the Israel-Hamas War

Market Analysis & Outlook: Cyclical Forces are Still in the Driver Seat

Conclusions & Positioning: Asset Allocation and Trade Set-Ups

The Economic Dial of Destiny

Barbie and Oppenheimer got all of the attention from critics and puntits this year, but another summer blockbuster movie that shouldn’t be overlooked was the The Dial of Destiny, the latest installment of the Indiana Jones franchise. We saw it on the big screen, and while falling short of Raiders of the Lost Ark, we found it to be entertaining and well-done, with great special effects and all of the usual gags, plot twists, and bravado that we’ve all come to expect from Harrison Ford and the gang at Lucas Films Ltd. The plot centers around a fictionalized version of an ancient device known as the Antikythera, purportedly invented by the Greek mathematician and inventor Archimedes, circa 212 B.C. In the film, the device built by Archimedes was designed to be a temporal mapping system across the space-time continuum. It was sought by the villain, a former Nazi scientist, as a way to travel back in time to help Germany win World War II.

But as some may know, the real Antikythera, is not a time machine at all, but an ancient Greek hand-powered model of the Solar System, often described as the oldest known example of an analog computer, and was probably used to predict astronomical eclipses and track cycles related to weather, agriculture, or perhaps even the Olympiad games. The artefact was discovered among items recovered by a group of sponge divers from a 2,000 year-old shipwreck off the coast of the Greek Island of Antikythera in 1901. A number of years ago, we had the opportunity to view many of the 82 fragments of the actual Antikythera mechanism at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, along with several reconstructions and replicas hypothesizing how the mechanism may have looked and operated in its original condition.

While an engineering marvel in its own right, the very existence of a device as complex as the Antikythera mechanism in the 2nd century B.C. demonstrates the importance to mankind of understanding cycles with precision. The Indiana Jones film makes an interesting assertion with respect to precision (spoiler alert). When the villain programs the dial based upon the space-time calculations that he believes will return him to 1942 Germany, Jones points out that his coordinates are wrong because they didn’t account for continental drift over the past two millennia. Archimedes didn’t know about the theory of plate tectonics because it wouldn’t even be conceived of until the late-16th century, when Abraham Ortelius first proposed the hypothesis that the earth’s continents have moved relative to one another over geologic time. In the end, the villain’s calculations missed the mark, and they landed in the middle of wrong war, and in the wrong century.

When attempting to understand the economic cycle with precision, one must also account for any change to the macro landscape — a sort of economic version of continental drift that also occurs over time. In the case of the macro landscape, those changes may include increases to the debt-to-GDP ratio, a rise in interest rates, or a shift in the relative value of one’s home currency. These are just a few of the variables that can, and do affect GDP growth, capital investment, and employment trends. If your understanding of the economic cycle does not account for changes in all of the relevant variables, you could miss the mark — just ask Fed chairman Jerome Powell.

Powell and the Fed missed their mark by a country-mile back in late-2021, when they ignored the empirical evidence at hand indicating that inflation was surging, and embraced a theory that the inflation surge would be short-lived and transitory. But that theory didn’t account for “continental drift.” The economic landscape had changed. We detailed those changes and the results of the Fed’s lack of precision back in Issue #23. Authorities have since been careful not to assert as much confidence in their views on the economy. Instead, “team transitory” has decided that they will remain data dependent with respect to future decisions toward increasing short-term interest rates. With monetary policy now as restrictive as its ever been in our 33-year career, we think that’s probably the best course of action. The majority of market participants now believe that the Fed is done raising rates, and may need to begin cutting them as early as June 2024. Yet, few believe that those cuts will be related to an oncoming recession, which in our view, could begin to reveal itself before the end of this year.

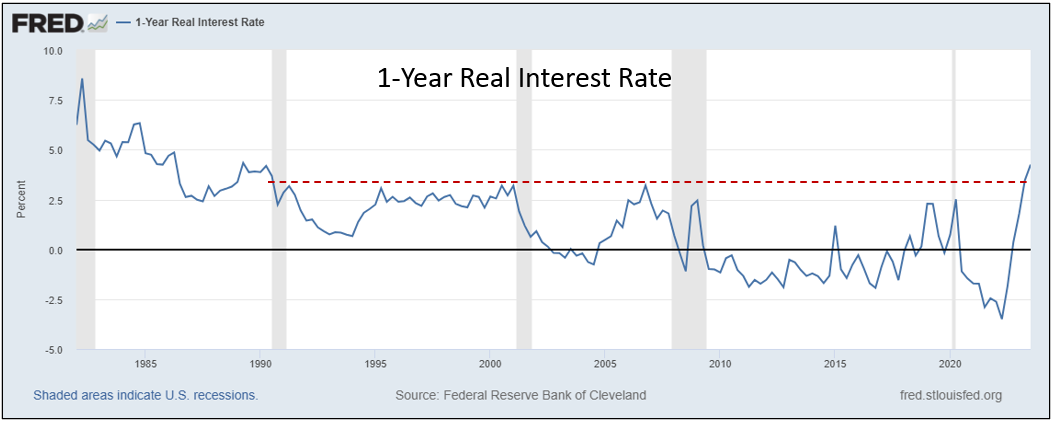

Indeed, the last time monetary policy was this tight it did lead to a recession, which began in Q3 of 1990 and ended three quarters later. In hindsight, its clear that the official onset of the 1990 recession began after the the 1-year real interest rate peaked and began to turn down. The 1-year real interest rate is like the economic version of the “dial of destiny.” In fact, a peak and reversal in the 1-year real interest rate has coincided with every recession over at least the past 40 years. But here’s a news flash: The current 1-year real rate has already begun to contract from its October inter-month high. By our work, we could witness a rather enthusiastic decline in the 1-year real rate if an economic recession unfolds in the U.S. over the next several quarters. We say if because, so far, a recession has remained elusive. But as discussed, monetary policy is now historically restrictive, and the last three U.S. recessions were attended by policy measures that were far less restrictive.

Moreover, the yield curve has re-steepened significantly over the past six months. The spread between the 10-year and the 2-year Treasury yields bottomed in June with a historically deep inversion of -106 bps, which has lasted for nearly 17 months, so far. It has been one of the most persistent yield curve inversions on record. The spread between the 10-year and the 3-month Treasury yields bottomed in April and was even more pronounced at -215 bps. The sharp recovery in these two spreads over the past few months to just -26 bps and -96 bps, respectively, is consistent with the onset of an economic recession. Indeed, an inverted yield curve has preceded each of the past six recessions by as few as 10, and as many as 33 months; it is the shot across the bow. But when the curve begins to re-steepen, that’s when you know for sure that the torpedoes are in the water!

One potential problem that we believe is still under recognized by Wall Street is the threat to financial stability associated with a so-called “bear steepening” of the yield curve. This occurs when the long-end of the curve rises and the short-end or the curve remains stable or rises less. Under this condition, low coupon, long-duration bonds will experience accelerating losses as the yield on longer maturity bonds rises due the convexity of the price-yield relationship. This could become a problem for a significant number of regional and money center banks whose held-to-maturity (HTM) portfolios are littered with legacy fixed-income assets acquired during the 2020-22 time frame before the Fed moved aggressively to raise rates in the face of surging inflation. According to Moody’s, as of the end of Q3, U.S. bank’s have at least $650 billion in unrealized losses on their balance sheets. Just to put that number into context, the government bailout of the entire U.S. banking system via the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) — authorized by The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, amounted to a mere $431 billion in disbursements when it was all said and done.

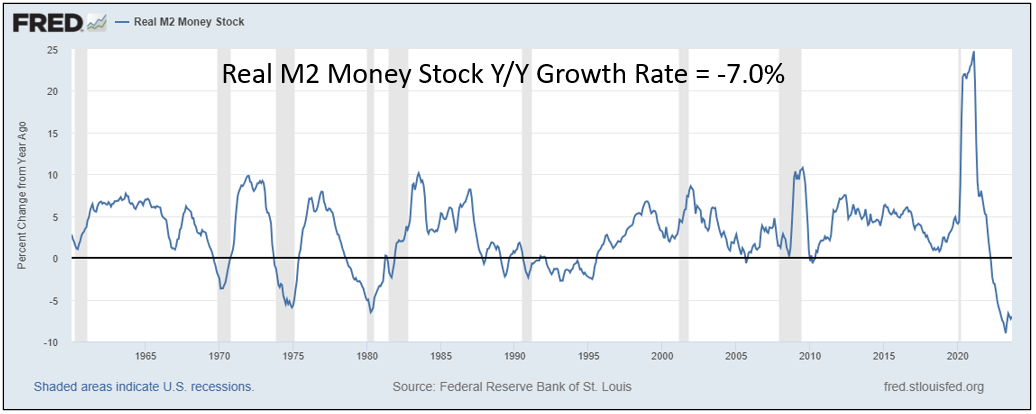

The real issue at hand is the overarching implication for liquidity conditions. When the banking system becomes impaired, as it now is, and lending standards tighten, as they have, then the Real M2 Money Stock contracts, as it clearly has — at a -7.0% Y/Y rate as of October. While not the worst reading we’ve seen in recent months, it is still worse than the prior worst episode in the history of the data going back to 1960. As such, we have questioned as to whether this evaporation of liquidity may be a prelude to a period of deflation in the years ahead. The concept of economic continental drift discussed above is a global phenomenon. China is already experiencing deflation at the producer price level — as is the Eurozone. This may sound like good news for corporate margins and consumer prices down the road, but once deflationary forces take root they are not easily reversed — just ask anyone living in Japan from 1990 to 2010.

The China Syndrome

We recently had an opportunity to debate a major China bull regarding the long-term outlook for Chinese equities. We argued the bear case defensibly, with facts and hard data, while the opposition pushed back by focusing on the overwhelming level of bearish sentiment toward China as being paramount to his case to buy. We can’t disagree that the consensus view toward China is quite bearish, but 70% of the time the consensus is right. We could say that the consensus view toward Russia is even more bearish, but we’d be hard pressed to find a Russia bull with whom to debate the matter. Bearish sentiment is not a reason to invest in a fundamentally bankrupt economy.

While Chinese manufacturing growth has disappointed for several years, the reshoring of many key U.S. manufacturing industries will only add to the pain. Indeed, select de-globalization will likely remain a trend for the next two decades. But, based upon our reading on the situation, the Chinese property market is the real problem, and it hangs by a thread. The importance of real estate to China’s economy should not be underestimated. It has been by far the greatest driver of wealth creation in China. It has also been by far the greatest driver of job creation in China. And it is by far the