Please enjoy the free portion of this monthly newsletter with our compliments. To get full access, you might want to consider an upgrade to paid for as little as $12/month. As an added bonus, paid subscribers also receive our weekly ALPHA INSIGHTS: Idea Generator Lab publication, which details our top actionable trade idea and provides updated market analysis every Wednesday, as well as other random perks, including periodic ALPHA INSIGHTS: Interim Bulletin reports and quarterly video content.

On May 11, 1997, an IBM computer known as “Deep Blue,” beat the world chess champion, Garry Kasparov, after a six-game match: two wins for IBM, one for Kasparov, and three draws. It was the classic plot line of man vs. machine. Behind the contest, however, was important new computer science known as “artificial intelligence” (AI). It was said at the time that the result constituted an historic breakthrough in AI research, which had the potential to perform the massive calculations necessary in many fields of science; to help discover new drugs; do the broad financial modeling needed to identify trends and do risk analysis; as well as handle large database searches.

Since the emergence of the first computers in the late 1940s, computer scientists have compared the performance of these “giant brains” with the human mind. They gravitated to chess as a way of testing the calculating abilities of computers. In 1989, IBM Research hired a team of graduate students at Carnegie Mellon University who had developed a chess playing machine called ChipTest, to continue their work and help other IBM computer scientists in what became known as project Deep Blue. They created a computer that could explore up to 200 million possible chess positions per second. In 1996, they challenged Kasparov to a match. The chess champion easily won the match. The team went back to the drawing board and used the lesson learned from that loss to improve Deep Blue’s knowledge of the game. The 1997 match was billed as a “rematch.” Kasparov confidently accepted, and the rest is history.

Ultimately, Deep Blue was retired to a Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C. But the Deep Blue project inspired a more recent grand challenge at IBM: building a computer that could beat the champions at a more complicated game — Jeopardy! Over three nights in February 2011, a new machine called Watson, took on two of the all-time most successful human players of the game and beat them in front of millions of television viewers. The technology in Watson was a substantial step forward from Deep Blue and earlier machines because it had software that could process and reason about natural language, then rely on the massive supply of information poured into it in the months before the competition. Watson demonstrated that a whole new generation of human-machine interactions will be possible.

Fast forward to November 30, 2022, and enter ChatGPT. ChatGPT is a Chatbot developed by OpenAI, an artificial intelligence research laboratory originally founded in 2015 as a non-profit backed by Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Sam Altman, and Microsoft, among others. OpenAI systems run on an Azure-based supercomputing platform from Microsoft. ChatGPT combines “Chat,” chatbot functionality, with “GPT,” which stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer — a type of large language model (LLM). The latest iteration — ChatGPT-4, is a task-specific GPT that was fine-tuned to target conversational usage.

The fine tuning process leveraged two machine learning paradigms including supervised learning, as well as reinforcement learning, to create a safer, more reliable experience that is 82% less likely to respond to requests for disallowed content, and 40% more likely to produce factual responses than its predecessor versions. Which brings us to the real issue with respect to this fascinating “new” technology — its key limitation is knowledge. Just like any other pre-trained model before it, GPT-4 is limited by its training data. It doesn’t know of events beyond September 2021, so GPT-4 may fail to provide accurate output if such output requires more recent information. Also, it can still “hallucinate,” (i.e. make up facts) and respond with flawed logic. In addition, it can’t solve complex mathematical problems. We recently spoke with a computer engineering PhD candidate from a top university who put it to us this way, “ChatGPT-4 is not artificial intelligence. In fact, it possesses no intelligence. It is a recursive algorithm with data parsing and classification abilities.”

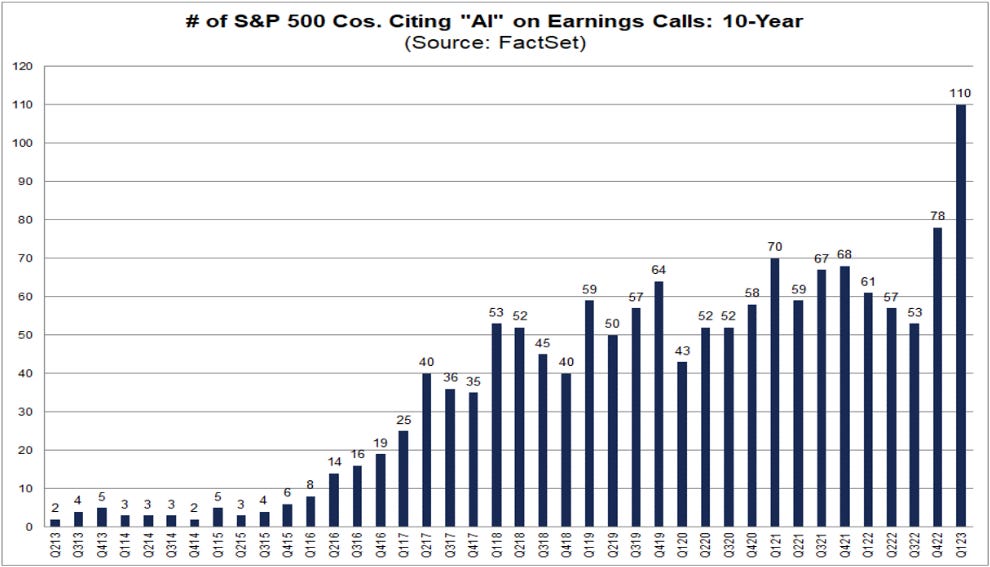

So, if ChatGPT is the latest and greatest discovery in computing — and its not AI, then why has there been a tidal wave of public companies citing “AI” on their earnings calls? The answer may be found in the history books. If we set the wayback machine to a period circa pre-2000, we would probably see a similar phenomenon with respect to the number of S&P 500 companies citing “Dot-Com” on their earnings calls. Indeed, just last year it was “ESG.” And before that, it was “Blockchain.” It is a serial desire for CEO’s of publicly traded companies to be seen as relevant in the eyes of their existing and prospective shareholders. And just as the fanciful Dot-Com dreams of many pre-2000 companies were shattered in the Tech Wreck that followed, so will the even more fantastical AI dreams of many of the fifty or so companies that suddenly glommed on to the new flavor of the day over these past six months.

The Magnificent Seven

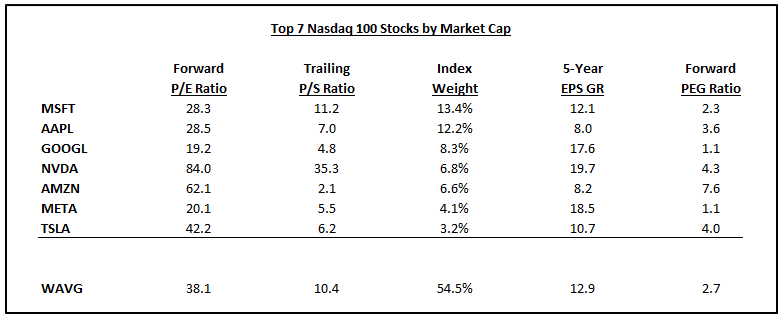

The winner’s circle with respect to AI will most likely include that select few, which have been most identified with this technology’s evolution long before it became popular to do so. We’ll call this group the magnificent seven. It includes MSFT, NVDA, GOOG, AMZN, TSLA, META, and of course AAPL. But is their leadership not yet priced in? The data below, which includes 1Q23 results and updated forward guidance would suggest that it has — and then some. In fact, boasting a P/E ratio of 84x and a P/E-to-Growth (PEG) ratio of 4.3x, the shares of NVDA appears to be pricing in the next decade’s results. The same could be said for AMZN and TSLA to some extent. The question isn’t whether or not AI will be the next big thing. It may, and probably will be over the next 25 years — just as the internet was over the last 25 years. The question is, what is it worth?

We think the answer is considerably less than the weighted average P/E of 38.1x that the magnificent seven trade at today. And there’s no guarantee that these high-priced, high flyers will continue to lead the charge. Just as CSCO, INTC, AOL, and HPQ are mere shadows today of their former selves, the possibility exists that even the mighty AAPL my someday go the way of IBM. The 1970s was another period in stock market history when money concentrated in just a few large-cap institutional darlings, known now as the Nifty Fifty. Then it was IBM, Xerox, Eastman Kodak, and Polaroid that were the must own at any price, cutting-edge Tech stocks of their day. Oh, how things can change. It brings to mind a quote from Ernest Hemingway, “How did you go bankrupt? Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

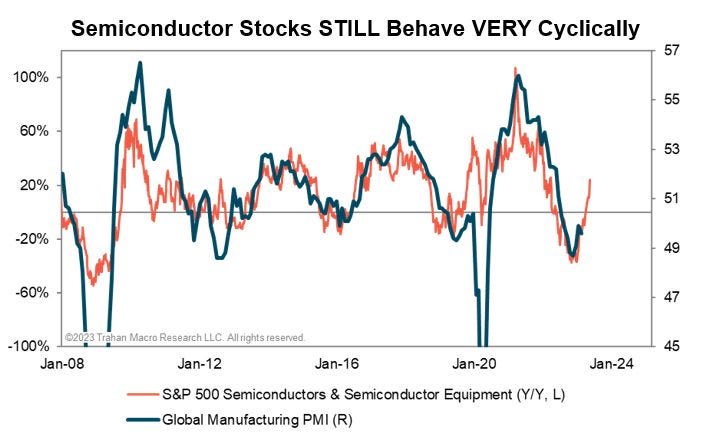

Not that we are suggesting any of the aforementioned companies is going to go bankrupt, it’s just that things can change abruptly. For example, NVDA is a semiconductor company that now accounts for over one-third of the market-cap of the semiconductor industry. It designs and sells graphic processing units (GPUs). Semiconductor industry revenues are highly cyclical. Since the semiconductor cycle is driven by macro forces, and monetary tightening points to lower demand, it is highly likely that the cycle has more downside than the stock is pricing in today. Indeed, NVDA’s share price has now deviated by >70% above its 200-day EMA. That is the second highest upside deviation recorded in the last 20-years. Past upside deviations of this magnitude have been followed by significant drawdowns in the stock price.

And it’s not just the stock’s recent price move that concerns us. NVDA CEO Jen-Hsun Huang’s revenue guidance for $11B in 2Q23, up $4B from the prior $7B expected, seems to contradict the 2Q23 guidance from Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC) for $15.2-16B, which is down $2B from the prior $17.6B expected. TSMC’s management cited, “customer’s further inventory adjustment.” For the uninitiated, that means that someone has been double ording product, which inflated perceived demand, resulting in a very large inventory build somewhere in the supply chain. Bear in mind that NVDA doesn’t manufacture their own GPUs. They outsource 100% of their GPU production to TSMC. So, if NVDA’s revenues are supposedly going to beat expectations by $4B next quarter, then why are TSMC’s revenues expected to miss expectations by $2B next quarter. It’s quite vexing.

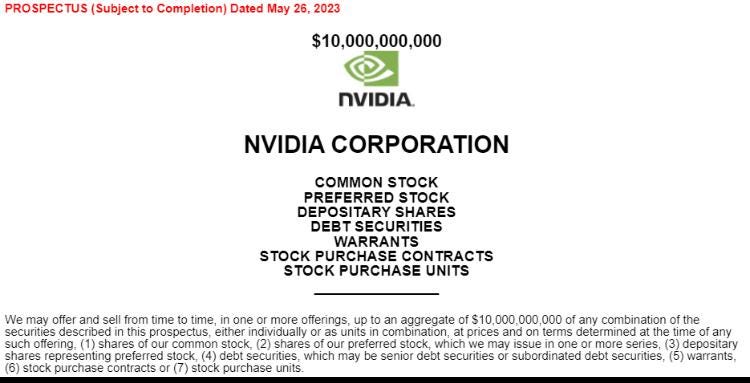

Yet, it should be no surprise that after the close on May 26th, following the stock’s euphoric reaction to their beat and raise quarter, NVDA management filed a shelf registration to to sell up to $10B of common stock. And why not, the company announced a $10B stock buyback last Fall, didn’t they? How does the saying go — buy low, sell high? If anything, Jen Huang has proven himself to be a savvy stock trader, having bought-back his shares all the way up from the lows last year. So, if he thinks its a good time to sell stock at 84x estimated EPS, then why would anyone want to be his bag holder? Before you decide to take the otherside of his trade, we recommend re-reading that cautionary tale published by Hans Christian Andersen back in 1837 entitled, The Emperor’s New Clothes. But enough about NVDA. Let’s examine the implications of the current AI hysteria for the rest of the stock market.