Please enjoy the free portion of this monthly newsletter with our compliments. To get full access, you might want to consider an upgrade to paid for as little as $12.50/month. As an added bonus, paid subscribers also receive our weekly ALPHA INSIGHTS: Idea Generator Lab publication, which details our top actionable trade idea and provides updated market analysis every Wednesday, as well as other random perks, including periodic ALPHA INSIGHTS: Interim Bulletin reports and quarterly video content.

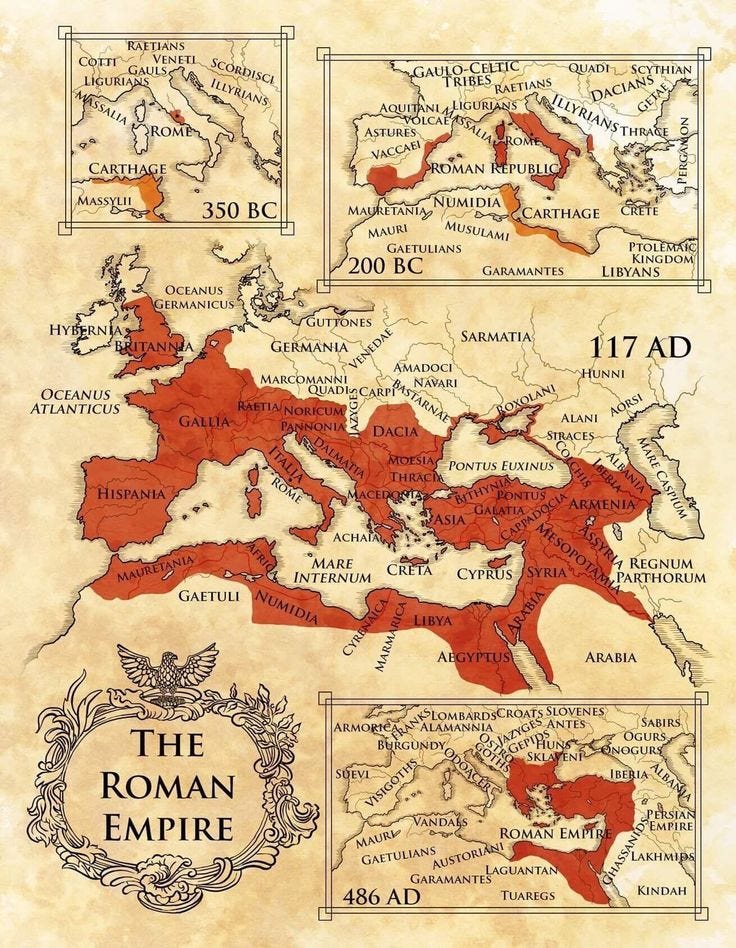

It’s been said that Rome was not built in a day. In fact, more than twelve centuries elapsed between the mythical birth of Remus and Romulus in 771 B.C. until the great republic-turned empire came to its unofficial conclusion in 476 A.D. But what led to its demise? Many scholars contend that the primary reasons for Rome’s decline and eventual fall were economic in nature. Two issues that stand out in the debate include the impact of currency debasement — coupled with a massive trade deficit between Rome and the Eastern Empire, and excessive taxation of its wealthiest citizens. Both ultimately served to stifle growth and prosperity in the West, which had far-reaching unintended consequences for Roman society.

Indeed, many of the economic circumstances facing the United States today bear a striking resemblance to the conditions leading up to the decline of Roman civilization. With respect to currency debasement, following an unprecedented level of monetary and fiscal policy support designed to revive the economy from the pandemic shutdown in 2020, the U.S. has experienced an inflationary shock that has effectively reduced the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar by approximately 20% when compared to its pre-pandemic purchasing power. While monetary policy has since reversed course, fiscal policy remains overtly supportive, as evidenced by the nation’s ballooning national debt and excessive budget deficit — despite strong employment trends and nominal GDP growth. And, while the top marginal federal income tax rate remains relatively low today compared with history, the Congressional Budget Office’s projected 10-year budget outlook would suggest that those tax rates are likely to increase in the not-too-distant future.

These large and seemingly-perpetual budget deficits echo the dole that Roman emperors maintained for centuries in order to solidify their political power. But the long-term consequences of that policy was dire. To put present day conditions into perspective, we’ve summarized some scholarly conclusions from historian Bruce Bartlett for your consideration below. Let’s take a deep dive into the rise and fall of the Roman empire. While you’re reading, try to think about how these events of the past parallel the present, and perhaps the future.

Bread and Circuses

Around the third century B.C., Roman economic policy started to contradict that in the Hellenistic world. In Greece, and especially Egypt, economic policy had become highly regimented, depriving individuals of the freedom to pursue personal profit in production or trade, imposing oppressive taxes, and forcing workers into vast collectives. The later Hellenistic period was one of almost constant warfare. The result was economic stagnation. Stagnation bred weakness among the Mediterranean states, which partially explains the ease with which Rome was able to steadily expand its reach. By the end of the first century B.C., Rome was the undisputed master of the Mediterranean. But Rome subsequently fell victim to civil wars, which eroded its strength.

Following the death of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C., his adopted son Octavian finally brought an end to internal strife with his defeat of Mark Antony in the battle of Actium in 31 B.C. However, years of war had taken a heavy toll on the Roman economy. Steep taxes and requisitions of supplies by the army, as well as rampant inflation and the closing of trade routes, severely depressed economic growth. Above all, businessmen and traders craved peace and stability in order to rebuild their wealth. Increasingly, they came to believe that this could only be maintained if political power were centralized in one man. This man was Octavian — who took the name Augustus, the first emperor of Rome (27 B.C. - 14 A.D.).

Although the establishment of the Roman principate represented a curtailment of political freedom, it led to an expansion of economic freedom. Augustus clearly favored private enterprise, private property, and free trade. The burden of taxation was significantly lifted by the standardization of taxation. Peace brought a revival of trade and commerce, further encouraged by Roman investments in good roads and harbors. Tiberius, Rome’s second emperor (14-37 A.D.), extended the policies of Augustus well into the first century A.D. It was his strong desire to encourage growth and establish a solid middle class, which he saw as the backbone of the empire.

Egypt, however, which was the personal property of the Roman emperor, largely retained its socialist economic system. The reason for this being that Egypt was the main source of Rome’s grain supply. Maintenance of this supply was critical to Rome’s survival, especially due to the policy of distributing free grain (and later bread) to all Roman citizens, which began in 58 B.C. By the time of Augustus, this dole was providing free food for some 200,000 Romans. The emperor paid the cost of the dole out of his own pocket, as well as the cost of games for entertainment, principally from his personal holdings in Egypt. The preservation of uninterrupted grain flows from Egypt to Rome was, therefore, a major task for all Roman emperors and an important base of their power.

The distribution of free grain and bread in Rome remained in effect until the end of the Empire. The expansion of the dole is an important reason for the rise of Roman taxes. In the earliest days of the Republic, Rome’s taxes were quite modest, consisting mainly of a wealth tax on all forms of property, including land, houses, slaves, animals, money and personal effects. The basic rate was just .01 percent, although occasionally rising to .03 percent. It was levied directly on individuals, who were counted at periodic censuses. In the provinces, however, the main form of tax was a tithe levied on communities, rather than directly on individuals. Local communities would decide for themselves how to divide up the tax burden among their citizens. Individuals knew in advance the exact amount of their tax bill and that any income over and above that amount was entirely theirs. This created a great incentive to produce, since the marginal tax rate above the tax assessment was zero. In economic terms, the tax system was pro-growth.

Rome’s pro-growth policies, including the creation of a large common market encompassing the entire Mediterranean, a stable currency, and moderate taxes, had a positive impact on trade. The increase in trade led to an increase foreign and inter-provincial maritime commerce, providing the main sources of wealth in the Roman Empire. There was a sharp increase in the Roman money supply, which accompanied the expansion of trade. This expansion of the money supply did not lead to higher prices. Interest rates also fell to the lowest levels in Roman history in the early part of Augustus’ reign. This strongly suggests that the supply of goods and services grew roughly in line with the increase in the money supply.

Pax Romana or Raubwirtschaft?

Under Claudius (41-54 A.D.) the Roman Empire added its last major territory with the conquest of Britain. Consequently, the state would no longer receive additional revenue from provincial tribute and any increase in revenues would now have to come from within the Empire itself. From this point on, the demand for revenue began to undermine the strength of the Roman economy. As early as the rule of Nero (54-68 A.D.), there is evidence that the demand for revenue led to debasement of the coinage. Revenue was needed to pay the increasing costs of defense and a growing bureaucracy. However, rather than raise taxes, Nero and subsequent emperors preferred to debase the currency by reducing the precious metal content of coins. This was, of course, a form of taxation — a tax on cash balances.

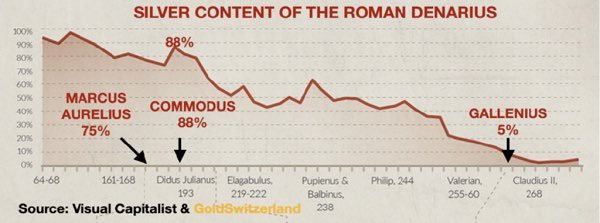

There were two main units of currency in the Roman Empire, the gold aureus, and the more common silver denarius. Debasement was mainly limited to the denarius. Nero reduced the silver content of the denarius to 90 percent and slightly reduced the size of the aureus in order to maintain the 25 to 1 ratio. Trajan (98-117 A.D.) reduced the silver content to 85 percent, but was able to maintain the ratio because of a large influx of gold. Debasement continued under the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161-180 A.D.), who reduced the silver content of the denarius to 75 percent, and it was further reduced by Septimius Severus to 50 percent. By the middle of the third century A.D., the denarius had a silver content of just 5 percent.

As the private wealth of the Empire was gradually confiscated or taxed away, driven away or hidden, economic growth slowed to a virtual standstill. Moreover, once the wealthy were no longer able to pay the state’s bills, the burden inexorably fell onto the lower classes, so that average people suffered as well from the deteriorating economic conditions. At this point, in the third century A.D., the money economy completely broke down. Yet the military demands of the state remained high. Rome’s borders were under continual pressure from Germanic tribes in the North and from the Persians in the East. Moreover, it was now explicitly understood by everyone that the emperor’s power and position depended entirely on the support of the army. Thus, the army’s needs took priority above all else, regardless of the consequences to the economy.

With the collapse of the money economy, the normal system of taxation also broke down. This forced the state to directly appropriate whatever resources it needed wherever they could be found. Food and cattle, for example, were requisitioned directly from farmers. Other producers were similarly liable for whatever the army might need. The result was a system in which individuals were forced to work at their given place of employment and remain in the same occupation, with little freedom to move or change jobs. The remaining members of the upper classes were pressed into providing municipal services, such as tax collection, without pay. And should tax collections fall short of the state’s demands, they were required to make up the difference themselves. This led to further efforts to hide whatever wealth remained in the Empire.

The steady encroachment of the state into the intimate workings of the economy also eroded growth. The result was increasing feudalization of the economy and a total breakdown of the division of labor. People fled to the countryside and took up subsistence farming or attached themselves to the estates of the wealthy, which operated as much as possible as closed systems, providing for all their own needs and not engaging in trade at all. By the end of the third century, Rome had clearly reached a crisis. The state could no longer obtain sufficient resources even through compulsion and was forced to rely ever more heavily on debasement of the currency to raise revenue. By the reign of Claudius II Gothicus (268-270 A.D.) the silver content of the denarius was down to just .02 percent. As a consequence, prices skyrocketed. A measure of Egyptian wheat, for example, which sold for seven to eight drachmas in the second century, now cost 120,000 drachmas. This suggests an inflation of 15,000 percent during the third century.

Finally, the very survival of the state was at stake. At this point, the emperor Diocletian (284-305 A.D.) took action. The cornerstone of Diocletian’s economic policy was to turn the existing ad hoc policy of requisitions to obtain resources for the state into a regular system. Since money was worthless, the new system was based on collecting taxes in the form of actual goods and services, but standardized into a budget so that the state knew exactly what it needed and taxpayers knew exactly how much they had to pay. Also, the tax burden was spread more widely, instead of simply falling on the unlucky, thus lowering the burden for many Romans. At the same time, with the improved availability of resources, the state could now better plan and conduct its military operations.

Sic Semper Tyrannis

Constantine (308-37 A.D.) continued Diocletian’s policies of regimenting the economy, by tying workers and their descendants even more tightly to the land or their place of employment. Despite such efforts, land was abandoned and trade, for the most part, ceased. Industry moved to the provinces, basically leaving Rome as an economic empty shell — still in receipt of taxes, grain and other goods produced in the provinces, but producing nothing itself. The mob of Rome produced nothing, yet continually demanded more, leading to an intolerable tax burden on the productive classes. In the fifty years after Diocletian the Roman tax burden roughly doubled, making it impossible for small farmers to live on their production. This is what led to the final breakdown of the economy. The number of recipients began to exceed the number of contributors by so much that, with farmers’ resources exhausted by the enormous size of the requisitions, fields were eventually abandoned.

The revenues of the state remained inadequate to maintain the national defense. This led to further tax increases, such as the increase in the sales tax from 1 percent to 4.5 percent in 444 A.D. However, state revenues continued to shrink, as taxpayers invested increasing amounts of time, effort and money into tax evasion schemes. Thus, even as tax rates rose, tax revenues fell, hastening the decline of the Roman state. In short, taxpayers evaded taxation by withdrawing from society altogether. Large, powerful landowners began to organize small communities around them. Small landowners, crushed into bankruptcy by the heavy burden of taxation, threw themselves at the mercy of the large landowners, signing on as tenants.

In the end, there was no money left to pay the army, build forts or ships, or protect the frontier. The barbarian invasions, which were the final blow to the Roman state in the fifth century, were simply the culmination of three centuries of deterioration in the fiscal capacity of the state to defend itself. Although the fall of Rome appears as a cataclysmic event in history, for the majority of Roman citizens it had little impact on their way of life. Indeed, many Romans welcomed the barbarians as saviors from the onerous tax burden. Once the invaders effectively had displaced the Roman government, they settled into governing themselves. At this point, they no longer had any incentive to pillage, but rather sought to provide peace and stability in the areas they controlled. After all, the wealthier their subjects the greater their taxpaying capacity.

The fall of Rome was fundamentally due to economic deterioration resulting from inflation, excessive taxation, and over-regulation. In comparison, the timeline to economic self-destruction in the United States might still look to be at least a few generations away. But what took Rome three centuries to accomplish, appears to have been achieved in about 110 years by contemporary central bankers, with the aid of “modern technology.” Since the inception of the Federal Reserve Board in 1913, monetary inflation has already diluted the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar by a full 96.7 percent. This monetary inflation was known as currency debasement in the 5th century parlance.

The Return of the Bond Vigilantes

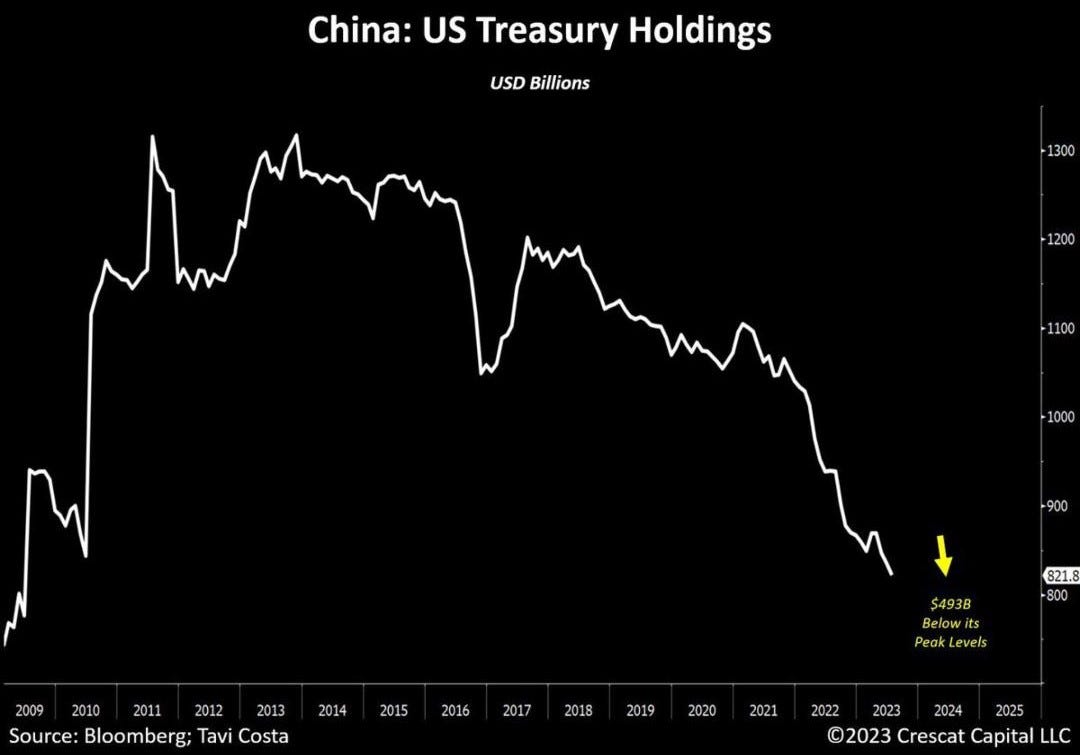

The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield posted a new 16-year high on Friday, rallying to a high of 4.89%. That’s about 164 bps above the April low of 3.25%. There have been a variety of explanations circulating abound Wall Street ranging from the narrowly averted government shutdown, to a major hedge fund liquidation, to foreign selling pressure due to the strong dollar, to retail and institutional selling pressure due to the massive supply overhang of expected future government issuance, to the impact of the Fed’s hawkish rhetoric and continued quantitative tightening, and our personal favorite —the unwinding of the Yen carry-trade, which we detailed in the September issue. All seem to be very plausible explanations, but also unlikely to have such a profound impact on their own. For example, the idea that China may be dumping U.S. Treasury notes is certainly plausible, but China has reduced their U.S. Treasury holdings by nearly $0.5 trillion over the last ten years — and by about $100 billion annually for the past three years. China and Japan only hold a combined 7.8% of outstanding U.S. Treasury debt — the lowest level on record.

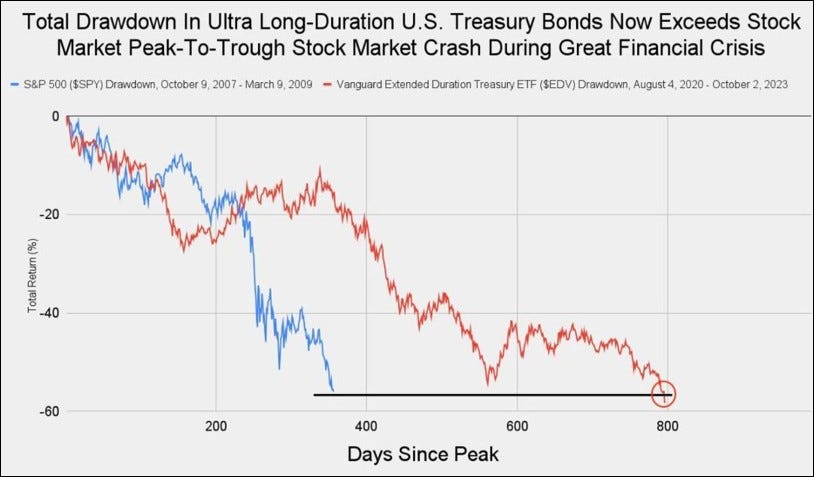

Most likely, it is a combination of all of the above mentioned accounts. One important consideration is the simple fact that the drawdown in U.S. Treasury bonds since their peak in August 2020, now exceeds the magnitude of the peak-to-trough decline in the S&P 500 index that took place during the Great Financial Crisis, and it has lasted more than twice as long. The significance of this should not be underestimated given the sheer size of the bond market. With every passing day, the pain of holding a long-term U.S. Treasury bond purchased anytime over the last five years grows more intense in the face of safe cash alternatives that may be yielding double, triple or even quadruple what a low coupon 30-year T-Bond might be paying. And to add insult to injury, investors must bear witness to the deep losses in their wealth every time they open a monthly statement or log into their account online. We took some time to review the Treasury bond inventories offered by several major investment banks, and were shocked to find that some long-dated, low coupon T-Bonds that were issued at par just three years ago are now offered at 45 cents on the dollar (e.g. UST 1.25% 5/15/2050) — ouch!

Just how much higher can rates climb? In our opinion, investors would be well-advised to respect the trend — and the trend is up and to the right. As we discussed in the September issue, a long-term technical case can be made for a continued rise in the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield to levels exceeding 10.5%. It probably won’t happen overnight, but rather in stages. We would expect the current advance to carry to approximately 5.3%, before the next sustained period of consolidation ensues. Our next upside target is above 6.0%, and we believe that it could be achieved sometime over the subsequent 12-months. While short-term volatility may result in violent countertrend pull-backs along the way, as long as the established sequence of higher-highs followed by higher lows persists, the path of least resistance is up.

There is one indicator that we’re watching closely for clues that yields may be topping