Please enjoy the free portion of this monthly newsletter with our compliments. To get full access, you might want to consider an upgrade to paid for as little as $15/month. As an added bonus, paid subscribers also receive our weekly ALPHA INSIGHTS: Idea Generator Lab publication, which details our top actionable trade idea and provides updated market analysis every Wednesday, as well as other random perks, including periodic ALPHA INSIGHTS: Interim Bulletin reports and exclusive video content.

Executive Summary

In Gold We Trust

Geopolitical Perspectives: A New World Bank

Election Inflection: The RFK Factor

Market Analysis & Outlook: Omega of the Alpha

Conclusions & Positioning: Panning for Gold

In Gold We Trust

The subtitle of this month’s newsletter, “A Rich Accounting of Money,” is intended as a tip of our hat to renowned Cambridge University cosmologist and theoretical physicist, the late-Professor Stephen Hawking. In his final interview with the BBC, Hawking explained how gold is formed from the collision of neutron stars:

“Gold is rare everywhere, not just on Earth. The reason it’s rare is that by nuclear-binding, energy peaks at iron, making it hard to produce heavier elements in general. Also strong electromagnetic repulsion must be overcome by the nuclear force in order to form stable heavy nuclei like gold.”

Of all the elements on the periodic table, gold has stood the test of time as the one that is best suited for use as money. It is scarce, malleable, durable, portable, divisible, and fungible. As money began to replace barter over the centuries, gold became the metal that was universally recognized as an object of value and therefore, an indispensable medium of exchange for social and economic progress. The unique nature of gold’s chemical properties make it indestructible, which is probably why gold has remained in use as money throughout the ages, and why it has superseded all other commodities. Its relative scarcity is key to gold’s quality as a long-term store of value. While the price of gold has periodically experienced extreme bouts of volatility, its limited supply has allowed gold’s value to remain relatively stable from age to age. For example, in 1924 a tailored suit of men’s clothing cost about one ounce of gold — then worth just $20.67. One hundred years later, in 2024, a comparable high quality, three-piece suit would run between $2,000 and $2,500, nearly the same price as an ounce of gold today.

As such, gold has garnered a reputation as a natural inflation hedge. In 1977, UC Berkeley economics professor Roy Jastram published The Golden Constant, the first detailed statistical study of gold’s properties as an inflation hedge. Using price data to back his findings — compiled from reliable sources dating to the year 1560, Jastram not only concluded that gold proved to be a reliable inflation hedge over long periods of time, but that it also proved to be a good deflation hedge as well. The reason for the latter, he determined, was that during periods of deflation there were much higher loan defaults as various counterparties within a liability chain failed to perform. As such, lenders and investors sought the stability of the one asset that was no one else’s liability — gold.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, only about 244,000 metric tons of gold has been discovered to date (187,000 metric tons historically produced plus current underground reserves of 57,000 metric tons). Most of that gold has come from just three countries: China, Australia, and South Africa. The United States ranked fourth in gold production in 2016. Perhaps surprising to some, all of the gold discovered thus far would fit into a cube that is 23 meters wide on all sides. According to the World Gold Council, most of the gold that is produced today goes into the fabrication of jewelry (50%), but gold is also an essential industrial metal that performs critical functions in computers, communications equipment, spacecraft, jet aircraft engines, and a host of other products (10%). The remaining new supply has been steadily accumulated by private investors in the form of coins and bars (30%), along with the world’s central banks (10%).

The United States Treasury has the single largest gold reserve on the planet at 8,133 metric tons. This amounts to a value of approximately $600 billion, as of April 30th. U.S. gold reserves are almost as substantial as the next three largest national gold reserves combined — those of Germany, Italy, and France, which have 3,355 metric tons, 2,452 metric tons, and 2,437 metric tons of gold, respectively. Over one-half of the U.S. Treasury’s gold is held at the United States Bullion Depository, a fortified vault building next to the U.S. Army post at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Another 20% of the Treasury’s gold is held at the West Point Mint, also located near a major U.S. military installation. Approximately 17% of the Treasury’s gold is held at the Denver Mint in Colorado. The final 7% of the nation’s gold reserve is held in the gold vault of the New York Federal Reserve Bank situated on the bedrock floor of Manhattan Island, set approximately 80 feet below street level and 50 feet below sea level.

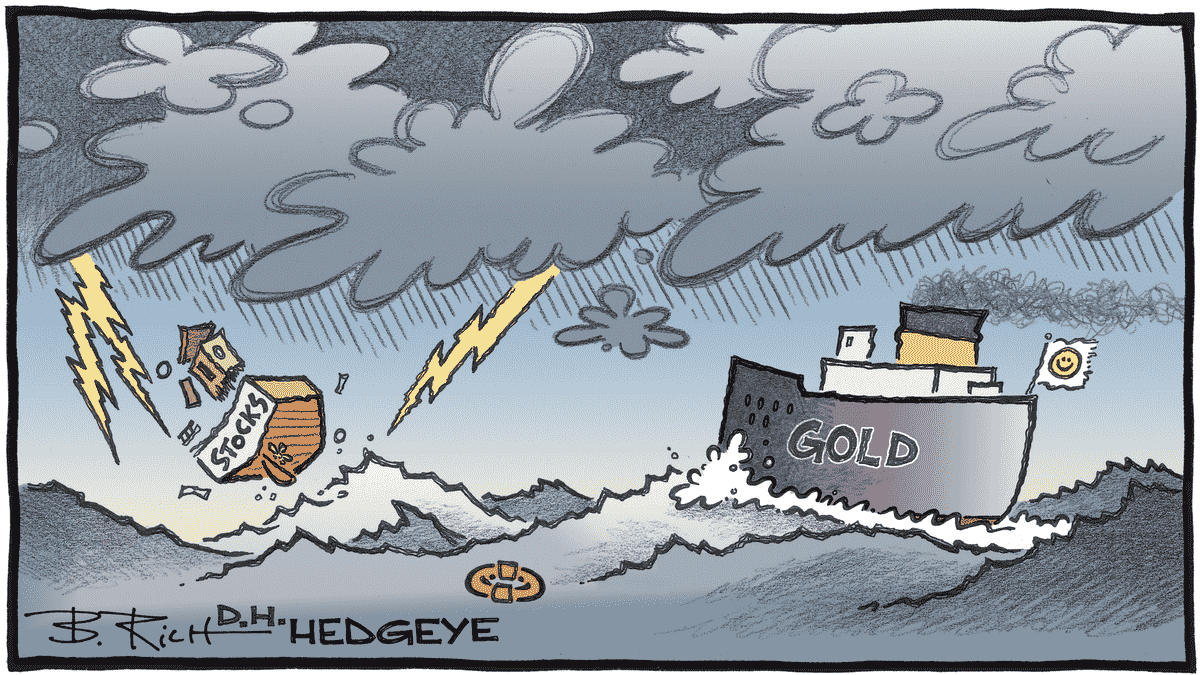

For untold millennia, gold has been valued as a global currency, a commodity, an investment, and simply an object of beauty. The first premeditated gold mining endeavors ever known to be conducted by man date back some six thousand years to North Africa, Mesopotamia, the Indus valley, and the eastern region of the Mediterranean. The earliest known gold objects belonged to the Egyptian culture circa 5000 B.C. But it was the Etruscan and Roman civilizations that brought true excellence to the production of gold objects and ornamentation, even before coinage.

The earliest knowns coins date back to 600 B.C. They were found by archeologists in the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus in modern-day Turkey. These ovular Lydian coins were made of a gold-silver alloy known as electrum and bore the image of a lion’s head. They were the forerunners of the Athenian tetradrachm, a standardized silver coin which bore the head of the goddess Athena on one side and the image of an owl on the other, presumably to denote her wisdom. By Roman times, coins were produced in three different metals: the aureus was minted of gold; the denarius of silver; and the sestertius of bronze. They were ranked in that order according to the relative scarcity of each metal, but all bearing the head of the reigning emperor on one side, and the legendary figures of Romulus and Remus on the other.

According to British historian A.H.M. Jones, the author of Inflation under the Roman Empire, in 89 B.C., one gold aureus was equal in value to 25 silver denarii; and one bronze sestertius was equal in value to one-quarter of a silver denarius. In A.D. 312, Constantine replaced the aureus with the solidus as the basic monetary unit. The solidus was struck at 4.55 grams of gold per coin. By that time the solidus was worth 275,000 denarii, which had been increasingly debased to just 5% of the silver content it had three and a half centuries beforehand. The Roman system of coinage actually outlived the Roman Empire itself. Prices were still being quoted in terms of silver denarii in the time of Charlemagne, circa A.D. 800. The difficulty was that by the time Charlemagne was crowned king of the Franks, silver had already become an important industrial metal, which led to a shortage in Western Europe. Indeed, gold’s emergence as the preeminent monetary unit of choice came about out of competition.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the subsequent Byzantine and Ottoman Empires continued the practice of minting gold as money. By the mid-thirteenth century, Italian city states had grown so wealthy from trade with India and China, that it enabled them to adopt gold as their monetary standard. Florence became the dominant issuer of gold currency in the region. The demand for florins throughout Europe incentivized the kingdom’s of Spain and Portugal — the dominant maritime hegemon’s of the era — to commission expeditions in search of new sources of gold.

When Spanish conquistadors returned from the new world with shiploads of precious metals plundered from the Aztecs, Incas, and Mayans, this created a huge new supply of gold and silver flowing through both Europe and Asia. In 1497, the Kingdom of Spain issued a silver dollar called the Real de a Ocho, or “pieces of eight,” which became a challenger to the florin as the dominant currency. The rapid increase in the supply of gold and silver coins in Europe led to the creation of the first public bank in Venice circa 1587, the Banco della Piazza di Rialto. Venetian bankers were renowned throughout Europe for perfecting the system of double-entry bookkeeping and conducting business through book entry transaction.

While gold had become the defacto monetary standard throughout the ancient world, Britain was the first country in the modern world to adopt the gold standard — although it was essentially an accident according to David Orrell, author of The Evolution of Money. In 1717, both gold and silver coins were in circulation throughout Britain, thus the Royal Mint was charged with setting the exchange rate between the two. Sir Isaac Newton, who at that time was Master of the Mint, set the exchange rate such that gold was overvalued relative to silver, and silver undervalued relative to gold. This led to a silver flight from Britain to Europe where silver was valued more highly than in Britain. Correspondingly, gold flowed into Britain from Europe since it was valued more highly there. While Britain was not formally on a gold standard in 1717, Newton’s move effectively placed them on one. Newton’s exchange rate put one gold guinea equal to 21 silver shillings — and there it remained for the next 200 years.

In 1783, King George III signed the Treaty of Paris, officially ending the American Revolutionary War, and recognizing the 13 colonies as the United States of America. Alexander Hamilton was appointed as the first Secretary of the United States Treasury in 1789. In his role, Hamilton suggested the formation of the country’s first national bank in 1791, and recommended the establishment of a mint. Because the most widely circulated coins in the U.S. at that time were Spanish currency, for simplicity’s sake, Hamilton proposed minting a U.S. currency that was of equal proportions and gold weight to that of the Spanish coins. The Coinage Act of 1792 adopted Hamilton’s principles leading to the minting of a ten-dollar gold eagle coin, a silver dollar coin, and fractional coins ranging from one-half a cent to fifty cents made of bimetallic currency of differing sizes struck at a fixed 15:1 silver to gold ratio.

Over the next century, a growing increase in silver production in the U.S. led to an expanding undervaluation of silver relative to gold, which in turn saw silver flow out of the U.S. and into foreign markets, while gold flowed into the U.S. from abroad. In 1873, the U.S. discontinued minting silver dollars, as had been authorized since 1792. By 1896 there was heavy resistance to the demonetisation of silver by a vocal pocket of American society. A bifurcation of economic fortunes within the U.S. following the Civil War, left farmers and industrialists at odds with one another. The lack of a silver-backed currency made access to capital scarce for western farmers following the panic of 1893, while the gold-backed currency flowed into manufacturing in the northeast. Pro-silver Democrats captured the party at the 1896 presidential convention, thrusting a gifted orator by the name of William Jennings Bryan into the limelight following his rousing “Cross of Gold” speech in Chicago that July.

Bryan had become the spokesman for farmers and laborers in the West and in the South. He talked only about money; only about silver — the money of the poor. Three times he ran for president on the Democratic ticket: First in 1896, then in 1900, and again in 1908. Bryan was narrowly defeated by former Ohio Governor William McKinley in the 1896 election — purportedly the result of some backroom political dealings undertaken by McKinley’s campaign manager, Mark Hanna. Later, a Midwest journalist by the name of L. Frank Baum, who covered the saga throughout the 1890s, decided to write an all-American children’s fairy tale, entitled The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, which he then published around the turn of the century. The story gained great notoriety thanks to the 1939 musical film starring Judy Garland. But in 1964, Amherst college professor Henry M. Littlefield brought some additional insight to the story, when he wrote an essay claiming Baum’s story was actually a political satire, pointing out the many parallels between the fairy tale and the political situation of the 1890s. Indeed, the subject is still vigorously debated by scholars to this day, perhaps best illustrated in a 1990 treatise authored by Rutgers University’s Professor Hugh Rockoff entitled, The “Wizard of Oz” as a Monetary Allegory.

But despite the best efforts of the free silver Democrats, the move to gold prevailed following the Gold Standard Act of 1900, making the U.S. the fourth major economy to officially adopt the gold standard following Russia, Germany, and Britain before it. By 1912, there were 49 countries on the gold standard, and if a country wasn’t on the gold standard themselves, then they likely held British Pounds as reserves, meaning their currencies were still effectively tied to gold. This system, up until the outbreak of World War I, is known as the classical gold standard — whereby a nation’s currency was defined by a fixed weight of gold, and paper money was freely convertible into gold by governments and private citizens alike. It was a period characterized by rapid economic growth, the free flow of labor and capital across borders, virtually free trade and, in general, world peace.

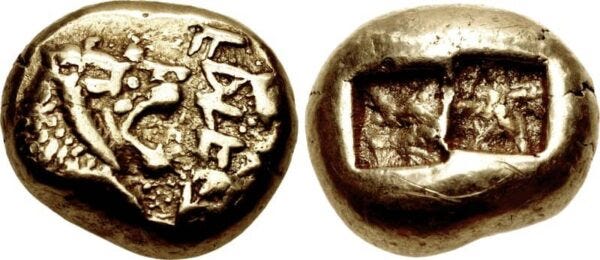

The outbreak of World War I was the end for the classical gold standard for Europe, as the combatants abandoned the mechanism that restrained their currency creation. Rather than finance the war through taxation, where their citizens might resist, governments preferred to use the inflation tax instead, and print the money needed to cover the deficits that financed the war. Of the major powers, only the U.S. remained on the pre-war gold standard. Four years of war caused economic devastation for those involved and the monetary policy used to finance the war left the participants’ currencies heavily devalued. By 1920, the British pound had lost 35% of its 1914 value, the Italian Lira fell 71%, and the French Franc fell 64%. Under the Weimar Republic, hyperinflation in Germany, due to the intractable burden of its war reparations during the early post-war years destroyed the Mark, which lost 96% of its value by the time Hitler embarked on his famous and ill-fated Beer Hall Putsch in November 1923.

In 1922, a conference was held at Genoa, where the European powers determined a new monetary system for the post-war environment. Plans were set in place for a return to gold. Britain was the first to make the move to gold in 1925, with other major powers following over the next few years. However, this was a very different system when compared to the classical gold standard. It became known as the gold-exchange standard. But it was a gold standard in name only. Instead of full-convertibility into gold, pounds could only be exchanged for gold by foreigners, and only in minimum denominations of one 400 ounce gold bar. Small denomination gold coins were strictly prohibited. This allowed governments to take control of the money supply. The U.S. had already taken control of its money supply through the creation of the Federal Reserve Bank in 1913 — a result of the 1907 financial panic, which left the government helpless to respond until J.P. Morgan stepped in to support the markets.

Making matters worse, Britain returned to gold at the wrong price. They tied their currency to gold at the pre-war price, not taking into account the massive expansion of the money supply since then. This, of course, did not work. It could not work unless Britain were to allow a currency contraction. But Britain continued an inflationary policy. The combination of an abandonment of the classical gold standard, the wartime inflation, and the disastrous post-war return to gold, all set the scene for a crisis that would unfold in the late-1920s culminating in the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression. While the gold standard has often been blamed for causing the Great Depression, and the end of the gold standard often credited with catalyzing the recovery, these are faulty arguments. A politically calculated gold price, coupled with an inflationary monetary policy were really what was responsible for the Great Depression. When gold is undervalued, central bank money is overvalued, and after reaching a tipping point the result is deflation.

The Federal Reserve then tried to inflate its way out of the Depression that was caused by Britain. Nervous Americans exercised their right to withdraw their savings from banks in gold. A bank run began in the United States — and in Germany and Austria as well. Gold was real money and people wanted the security of physical possession. In 1931, Britain, Germany, and Austria abandoned the new gold standard, as did 25 other countries. Under newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the U.S., who had stuck to the classical gold standard in 1914, finally gave in. Roosevelt put an embargo on the export of gold, made it illegal for private citizens to hold gold, and raised the price from $20.67 to $35 per ounce. It might be more accurate to say that Roosevelt dramatically devalued the dollar rather than raised the price of gold. This was still a gold standard in a loose sense, since the U.S. dollar was still tied to gold, but since there was no free convertibility and citizens could not hold gold it became a gold standard in name only. Gold was no longer considered money, but essentially became a reserve asset only.

The world’s monetary system changed again as a result of World War II. While U.S. economic standing in the world had risen after World War I, by the end of War World II, the U.S. was the sole economic superpower. Russia was still a dominant political and military force, but they were financially devastated and their economy was closed. This meant the U.S. could essentially dictate the new rules of the game. At the Bretton Woods conference in 1944 it was decided that foreign currencies would be tied to the U.S. dollar at fixed rates. This formally made the U.S. dollar the world’s reserve currency. Gold still played an important role in the global monetary system because foreign governments were still free to redeem their U.S. dollars for gold at $35 per ounce. This meant that by holding U.S. dollars as reserves, a foreign government still had a tie to gold even if they had abandoned the gold standard themselves.

For the Bretton Woods system to work, it required a lot of trust in the United States government. Foreign governments holding U.S. dollar reserves had to trust that the U.S. would keep their money supply stable so that the fixed-rate of $35 per ounce reflected the actual market price for gold in dollars. Not surprisingly, the U.S. abused its monetary privilege and heavily inflated its currency in the decades following the war. Had gold traded freely on the market, the price would have been much higher than $35 per ounce. Yet, since the U.S. government had pledged at Bretton Woods to redeem one ounce of gold for $35, several shrewd European governments realized that their U.S. dollar reserves were falling in value and decided to redeem their U.S. dollars for gold.

This was a problem for the United States. The U.S. couldn’t accept such significant outflows of gold. But this option to redeem dollars for gold hindered their ability to print money. The U.S. had only two choices. Either they could contract the money supply and be disciplined, or they could just stop allowing foreign governments to redeem their dollars for gold. The U.S. chose the latter. In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson ended the existing requirement for 25% of the money supply to be held as gold reserves. In 1971, President Nixon then ended the convertibility of dollars into gold, and thus severed the last formal tie between the U.S. dollar and gold. Nixon also devalued the dollar further by adjusting the gold price from $35 per ounce to $38, and then to $42.22 by 1973. Despite the fact that gold trades freely at market prices significantly higher, that is still the price at which gold is valued today on the Treasury’s books.

During his days as an Ayn Rand disciple, a young Alan Greenspan wrote a five page manifesto entitled, Gold and Economic Freedom, where he vehemently argued in favor of a gold standard as the only reliable means to protect an economy’s stability and balanced growth against unchecked inflationary monetary policies.

“A free banking system based on gold is able to extend credit and thus to create bank notes (currency) and deposits, according to the production requirements of the economy. Individual owners of gold are induced, by payments of interest, to deposit their gold in a bank (against which they can draw checks). But since it is rarely the case that all depositors want to withdraw all their gold at the same time, the banker need keep only a fraction of his total deposits in gold as reserves. This enables the banker to loan out more than the amount of his gold deposits (which means that he holds claims to gold rather than gold as security of his deposits). But the amount of loans which he can afford to make is not arbitrary: he has to gauge it in relation to his reserves and to the status of his investments.”

Greenspan detailed the rationale for the creation of the Federal Reserve System as a cure to the sharp, but short-lived recessions that interrupted economic growth due to the strict nature of a classical gold standard.

“If a shortage of bank reserves was causing a business decline — argued economic interventionists — why not find a way of supplying increased reserves to the banks so they never need be short! If banks can continue to loan money indefinitely — it was claimed — there need never be any slumps in business.”

But, he then explained that those sharp, but short-lived recessions were themselves the actual cure to runaway credit creation. They were misdiagnosed by economic interventionalists as the disease in Greenspan’s view. Then he delivered the punchline: