Please enjoy the free portion of this monthly investment newsletter with our compliments. To get full access, you may want to consider an upgrade to paid for as little as $15/month. As an added bonus, paid subscribers also receive our weekly ALPHA INSIGHTS: Idea Generator Lab report, an institutional publication that provides updated market analysis and details our top actionable ETF idea every Wednesday. Thanks for your interest in our work!

Executive Summary

Rope-a-Dope

Macro Perspectives: Reciprocal Stagflation

Geopolitics: Let the Games Begin

Market Analysis & Outlook: A New Bear Market

Conclusions & Positioning: The Perfect Portfolio

Rope-a-Dope

Heading into the month of March, the bull market must have seemed to investors as George Foreman seemed to boxing fans back in 1974 — invincible! The Foreman vs. Ali match was a foregone conclusion in the minds of almost everybody on the planet, just as 20% annual stock market returns were until recently. How could a washed-up old has-been like Muhammed Ali expect to beat the 40-0 undefeated George Foreman, when his younger, more agile self couldn’t even defeat the 26-0 Joe Frazier — a man Foreman knocked out in two rounds? Sure, the S&P 500 was down 3% for the year, but it was ahead on points — AI, Trump’s new ‘America First’ economic platform, and cooling inflation. Foreman too was still ahead on points going into round seven, but like the S&P 500, he was showing signs of fatigue. Akin to the onset of a bear market decline, just before the bell rang, the underestimated Ali landed a decisive combination to even up the score. Fast-forward to the eighth round, with just 20 seconds remaining, and Bob Sheridan’s colorful play-by-play commentary explains just how that story ended:

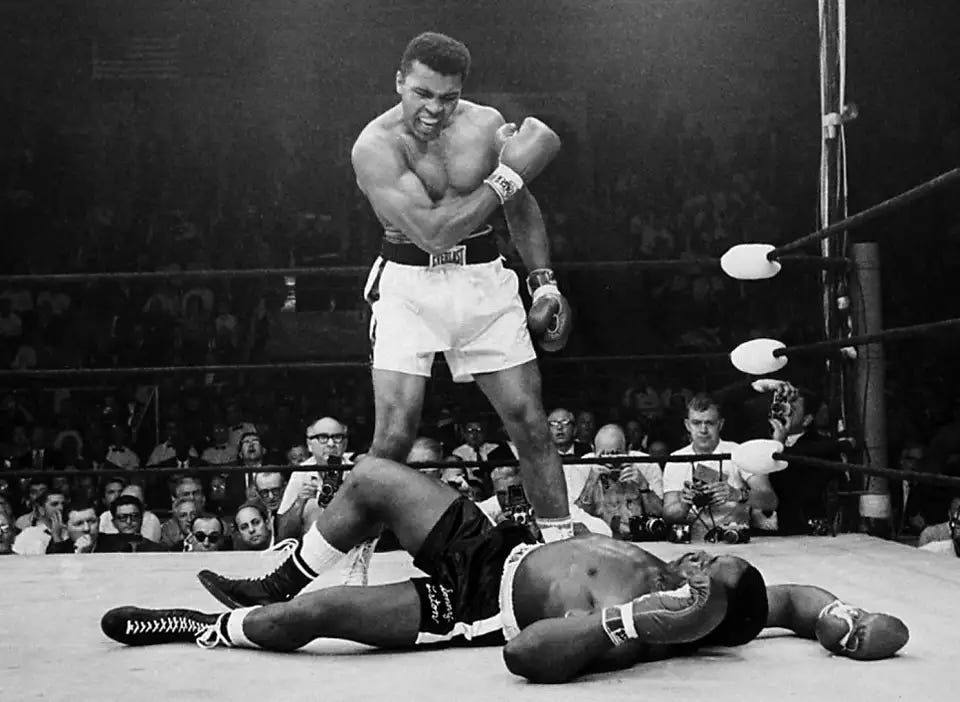

“Oh, he’s got him with a right hand, oh you can’t believe it… Ali’s doing his shuffle and I don’t think Foreman’s going to get up… he's trying to beat the count… and he’s out! Oh my God, he’s won the title back at 32! He took on Foreman at his own game and he beat him at it! I haven't seen anything like this in my life.”

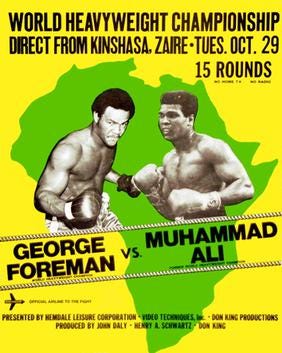

The so-called “Rumble in the Jungle,” was a heavyweight championship boxing match that took place on October 30, 1974, at what is now the Stade Tata Raphaël in Kinshasa, Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo), between the undefeated and undisputed heavyweight champion George Foreman and the former heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali. The event had an attendance of 60,000 people and was one of the most watched televised events of its day with an estimated 1 billion viewers, grossing $100 million in worldwide revenue (or about $644 million in today’s dollars). Ali won by knockout, eight rounds into the scheduled fifteen round bout, in what has been called “arguably the greatest sporting event of the 20th century.” It was a major upset, with Ali coming into the fight as a four-to-one underdog against the unbeaten, heavy-hitting Foreman. The fight became famous for Ali’s introduction of the “rope-a-dope.”

In 1967, then-champion Muhammed Ali was stripped of his title and suspended from boxing for three years due to his refusal — as a conscientious objector — to comply with the draft and enter the U.S. Army. In 1970, he regained his boxing license and promptly fought comeback fights against Jerry Quarry and Oscar Bonavena in an attempt to win back the heavyweight championship from the then-undefeated Joe Frazier. In a bout dubbed the Fight of the Century, Frazier won a unanimous decision, leaving Ali fighting other contenders for years in an attempt at a new title shot.

Meanwhile, the heavily muscled Foreman had quickly risen from a gold-medal victory at the 1968 Olympics to the top ranks of the heavyweight division. Greatly feared for his punching power, size, and sheer physical dominance, Foreman was nonetheless underestimated by Frazier and his promoters, and knocked the champion down six times in two rounds before the bout was stopped. He further solidified his hold over the heavyweight division by knocking out the only other man besides Frazier at that time to defeat Ali — Ken Norton — also in two rounds. At 25, the younger, stronger Foreman seemed an overwhelming favorite against the well-worn 32-year-old Ali.

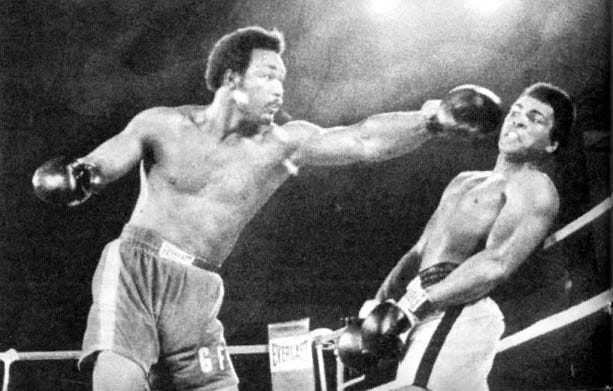

While Foreman’s raw power was his greatest strength, Ali was famed for his speed and technical skills. Defying convention, when the bell rang, Ali began the round by attacking Foreman with disorienting right-hand leads. This was notable as it seemed that close-range fighting would inevitably favor Foreman and his powerful haymakers. Ali made use of the right-hand lead punch (striking with the right hand without setting up the left) in a further effort to disorient Foreman. However, while this aggressive tactic may have surprised Foreman and allowed Ali to punch him several times in the head, it failed to significantly hurt him. Before the end of the first round, Foreman began to catch up to Ali, landing punches of his own. Foreman had been trained to cut off the ring and prevent escape. Ali realized that he would tire if Foreman could keep making one step to Ali’s two, so he changed tactics.

Ali had told his trainer and his fans that he had a secret plan for Foreman. As the second round commenced, Ali began to lean on the ropes and cover up, letting Foreman punch him on the arms and body — a strategy Ali later dubbed the rope-a-dope. As a result, Foreman spent his energy throwing punches (without earning points) that either did not hit Ali or were deflected in a way that made it difficult for Foreman to hit Ali’s head, while sapping Foreman’s strength due to the large number of punches he threw. This loss of energy was key to Ali’s rope-a-dope tactic.

During the interval, Ali took every opportunity to land straight punches to Foreman’s face (which became visibly puffy). When the two fighters were locked in clinches, Ali consistently out-wrestled Foreman, using tactics such as leaning on Foreman to make Foreman support Ali’s weight, and holding down Foreman’s head by pushing on his neck. He constantly taunted Foreman in these clinches, telling him to throw more punches, and the enraged Foreman responded by doing just that.

After several rounds of this, Foreman began to tire. His face became increasingly damaged by hard, fast jabs and crosses by Ali. The effects were visible as Foreman was staggered by an Ali combination at the start of the fourth round, and again several times near the end of the fifth, after Foreman had seemed to dominate that round. The film of the fight shows Foreman striking Ali with hundreds of thunderous blows, many blocked, but many others getting through. Although Foreman kept throwing punches and coming forward, after the fifth round, he looked increasingly worn out. Ali continued to taunt him by saying, “They told me you could punch, George!” and “They told me you could punch as hard as Joe Louis.” According to Foreman: “I thought he was just one more knockout victim until, about the seventh round, I hit him hard to the jaw and he held me and whispered in my ear: ‘That all you got, George?’ I realized that this ain’t what I thought it was.”

As the fight drew into the eighth round, Foreman’s punching and defense became ineffective as the strain of throwing so many wild shots took its toll. Ali pounced as Foreman tried to pin Ali on the ropes, landing several right hooks over Foreman’s jab, followed by a five-punch combination, culminating in a left hook that brought Foreman's head up into position and a hard right straight to the face that caused Foreman to stumble to the canvas. Foreman rose to one knee but referee Zack Clayton signaled the end of the fight before Foreman got to his feet. At the stoppage, Ali led on all three scorecards by 68–66, 70–67, and 69–66.

Some people consider boxing to be a brutal and disgusting display of violence, but in fact it’s statistically less violent than football. In many ways, besides being an athletic competition of skill and endurance, it represents an art form, a science, and a branch of economics, if not a microcosm of capitalism, and perhaps even life itself. Bull markets and bear markets are a lot like two prizefighters slugging it out in the ring. In the case of the current bear market decline, its cunning skills of deception rival those of Ali, leaving market bulls fooled by its rope-a-dope tactic. Gradually, it wore down the enthusiasm of the bulls by allowing the ropes to absorb each rally attempt from December 6th to February 19th without making any significant headway. To be sure, it almost fooled us. But by the close of business on February 27th, important moving averages had been breached and key trend lines broken. That, coupled with the many other warning signals that we’ve been discussing in these pages over the preceding months, made it abundantly clear to us that the bull market had taken a few too many shots to the head and was now staggering. At the same time, investors were also beginning to realize that maybe the February high “ain’t what they thought it was.”

From that point forward, the S&P careened lower by nearly 500 points or 8% into the mid-March low. By the end of the month, prices had declined by 10.7% from the February 19th intraday high to the March 31st intraday low. Following a torrid three-day rally that re-traced about one-third of the entire decline off the February peak, investors reacted to President Trump’s reciprocal tariff policy announcement by rushing to the exits again. By the close on April 4th, the S&P 500 had experienced a peak-to-trough decline of nearly 17%, while the Nasdaq 100 has plunged by over 21%. Meanwhile, media commentators have been endlessly trying to call the market’s bottom since the decline began, listing the names of “great” companies now available at “cheap” prices, and citing the AI narrative, robust earnings expectations, and resilient consumer spending, as reasons to remain bullish.

Following a 17-21% decline in stock prices, believe us when we say, the consumer is no longer resilient. His spending power has been cut-off at the knees and he is now curled up in the fetal position wondering how he is going to pay for his family vacation to Disney World this summer. After 35-years trading markets, we know from experience that the financial media and Wall Street are always bullish on the way down. It’s not until they fully capitulate and become hysterically bearish that we’ll know that the bottom is near. Market strategists on CNBC today have only reached neutral. They have not yet capitulated. By our count, the bear market decline is just getting started and may have a long way to go before finding a truly durable low.

Below we’ll discuss why we think the risk of stagflation is rising, and how this could push the U.S. economy into recession. We will also discuss why we think the reordering of U.S. trade policy objectives probably won’t improve the U.S. economic position — and instead may impair it. In addition, we’ll overlay key cycle studies that support the case for a major bear market in stocks that could last for years — and possibly a decade or more. Finally, we’ll detail how investors should position their portfolios today, in order to thrive during what promises to be a tumultuous period ahead.

Let’s begin…