Please enjoy the free portion of this monthly newsletter with our compliments. To get full access, you may want to consider an upgrade to paid for as little as $15/month. As an added bonus, paid subscribers also receive our weekly ALPHA INSIGHTS: Idea Generator Lab publication, which provides updated market analysis and details our top actionable trade idea very Wednesday, as well as other perks, including periodic ALPHA INSIGHTS: Interim Bulletin reports and exclusive video content.

Executive Summary

The Man Who Sold the World

Economic Overview: Permanent Waves

Geopolitical Perspectives: China Grove

Market Analysis & Outlook: All Apologies

Conclusions & Positioning: Silver & Gold

The Man Who Sold the World

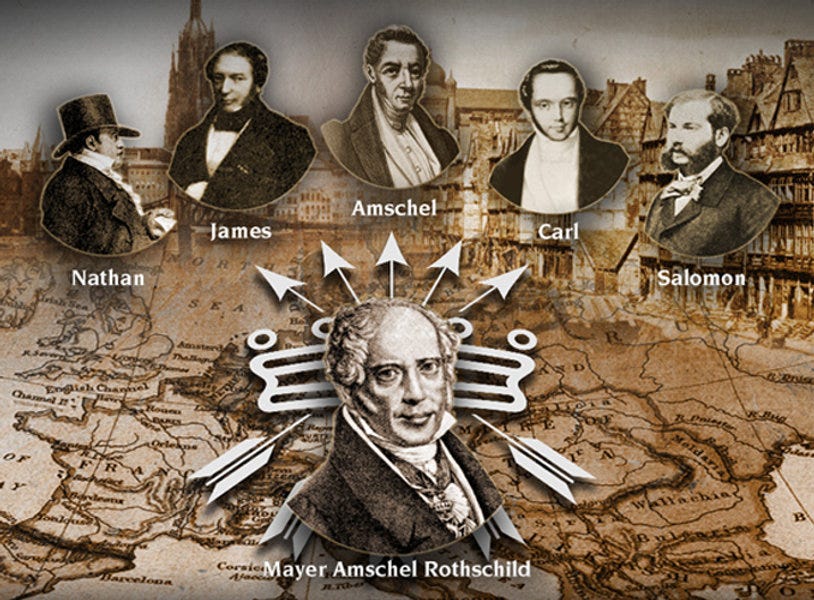

The Rothschild family can trace its roots back to a Jewish ghetto in Frankfurt circa 1567, where Isaak Elchanan Bacharach was the first to use the name Rothschild. The name was derived from the German zum rothen schild — meaning “at the red shield” — in reference to the sign designating the address of his generational family home. A red shield can still be found at the center of the Rothschild coat of arms.

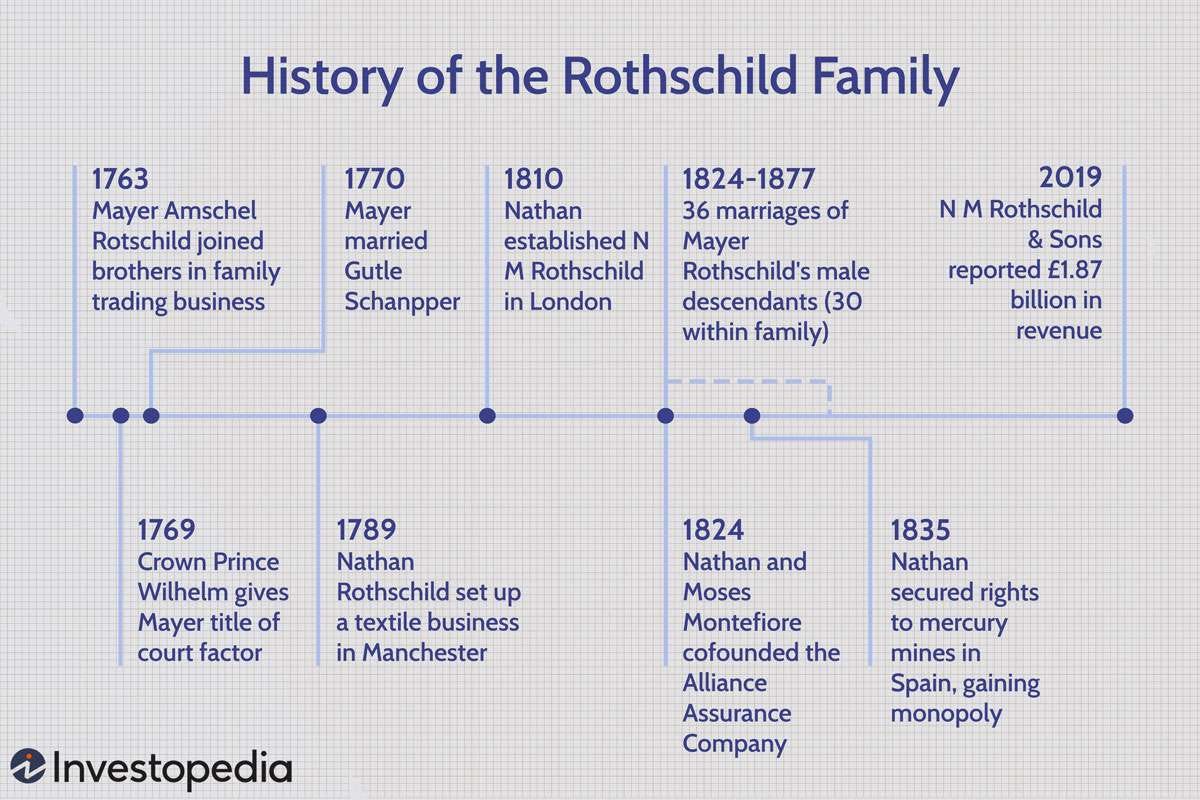

But the family’s ascent to prominence did not begin until 1744, with the birth of Mayer Amschel Rothschild, who joined his family’s trading business as a money changer in 1763. Mayer developed the finance house and expanded his empire by installing his five sons in the five main European financial centers to conduct business: Amschel stayed in Frankfurt; Salomon was sent to Vienna; Nathan to London; Carl to Naples; and James to Paris. The coat of arms contains two clenched fists — each holding five arrows. One symbolizes the five sons, the other symbolizes the five banking dynasties that they established.

The success of the Rothschild banking dynasty has become the subject of legend within the realm of finance. Many wonder how it was possible for Mayer Rothschild to transcend the same perils to which so many others succumbed. According to historian Paul Johnson, unlike the Jewish financiers of earlier generations — who had also financed and managed European noble houses, but often lost their wealth through violence or expropriation — the new kind of international bank created by the Rothschilds was impervious to local attacks. Their assets were held in financial instruments, circulating through the world as stocks, bonds and debts. Changes made by the Rothschilds allowed them to insulate their property from local violence. Johnson wrote:

“Henceforth their real wealth was beyond the reach of the mob, almost beyond the reach of greedy monarchs.”

Another essential part of Mayer Rothschild's strategy for success was to keep control of their banks in family hands through carefully arranged marriages to first or second cousins (similar to royal intermarriage), allowing them to maintain full secrecy about the size of their fortunes. This practice was later copied by a number of Jewish financiers including the Bischoffsheims, Pereires, Seligmans, and Lazards, which allowed the Jewish banking fraternity — headed by the Rothschilds — to dominate international finance in the late-19th century.

The truth about the origins of the Rothschild’s fortune is elusive. There are no revealing or accurate books written about the details of their banking success — although reams of nonsense have been written about the family’s purported business endeavors. And while it is a fact that all five of Mayer’s sons were successful at financial deal making, one son in particular stood head and shoulders above the others — if not only by his mercurial reputation alone. That son was Nathan Rothschild.

The Rothschilds already possessed a significant fortune before the start of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), but the family gained preeminence in the bullion trade during that time. From London in 1813 to 1815, Nathan Rothschild was instrumental in almost single-handedly financing the British war effort, organizing the shipment of bullion to the Duke of Wellington’s armies across Europe, as well as arranging the payment of British financial subsidies to their continental allies. In 1815 alone, the Rothschilds provided £9.8 million (about $600 million today) in subsidy loans to Britain’s continental allies. The five brothers all helped coordinate Rothschild activities across the continent, and the family developed a network of agents, shippers and couriers to transport gold across war-torn Europe. The family network was also to provide Nathan Rothschild time and again with political and financial information ahead of his peers, giving him an advantage in the markets and rendering the house of Rothschild ever more invaluable to the British government.

In one instance, the family network enabled Nathan to receive the news in London of Wellington’s victory at the Battle of Waterloo a full day ahead of the government’s official messengers. Rothschild’s first priority on this occasion was not the potential advantage in the financial markets that the knowledge would have given him. In fact, according to historian Niall Ferguson, he and his courier immediately took the news to the government. That he used the news for financial advantage is a now popular anti-semitic fiction propagated by the Nazis. In 1940, Joseph Goebbels approved the release of Die Rothschilds, which depicts an oleaginous Nathan bribing a French general to ensure the Duke of Wellington’s victory, and then deliberately misreporting the outcome in London in order to precipitate a panic selling of British bonds, which he then snapped up at bargain basement prices. That’s not what happened, yet the story was further perpetuated in Frederic Morton’s 1962 expose, The Rothschilds: A Family Portrait.

As detailed in Niall Ferguson’s The World’s Banker: A History of the House of Rothschild, the basis for the Rothschilds’ most famously profitable move was made after the news of British victory had been made public. Indeed, Nathan Rothschild was in a difficult situation, having amassed as much gold as he could buy at fairly high prices in order to provide hard currency to the front lines. With the war now won, there was no longer the same pressing need for gold, and prices began to sink. Nathan calculated that the future reduction in government borrowing brought about by the peace would create a bounce in British government bonds after a two-year stabilization, which would finalize the post-war restructuring of the domestic economy.

In what has been described as one of the most audacious moves in financial history, Nathan Rothschild immediately bought up the government bond market, for what at the time seemed an excessively high price. He sat on the bonds for two years as expected, then sold out his position at the crest of a short-term bounce in the market in 1817 for a 40% profit. Given the sheer power of leverage the Rothschild family had at their disposal, this profit was an enormous sum — in the tens of millions of pounds (equating to billions of dollars today). There is an infamous quote that is often attributed to Nathan Rothschild:

“The time to buy is when there’s blood in the streets.”

And while it’s possible that he said it, there is no evidence to support the claim that Nathan Rothschild ever made that statement.

Nathan Rothschild established N. M. Rothschild & Sons in 1810. In 1818, he arranged a £5 million loan to the Prussian government (about $350 million today), and ever since that time, the underwriting of government debt sales has formed a mainstay of his bank’s business. He gained a position of such power in the City of London that by 1826 he was able to supply enough coin to the Bank of England to enable it to avert a market liquidity crisis. On September 29, 1822, all five of Mayer Amschel Rothschild’s sons were granted the hereditary title of Baron by Emperor Francis I of Austria.

Since the late-19th century, the family has maintained a low-key public profile, donating many famous estates — such as Waddesdon Manor, as well as vast quantities of art, to charity, and generally abstaining from conspicuous displays of wealth. Today, Rothschild businesses are of smaller scale than they were throughout the 19th century, although they encompass a diverse range of fields, including: real estate, financial services, pharmaceuticals, mixed farming, energy, mining, winemaking and nonprofits. By some estimates, the family’s fortune is said to have a current net value of $1.2 trillion. Nearly 300 years of inflation has been very kind to property owners.

Economic Overview: Permanent Waves

On November 5th, registered voters across the U.S. will line-up at their respective polling places to cast their vote for the next President of the United States, along with a host of other down-ballot candidates running for government office. The stakes are always high, but this election seems to be one that will rank near the tippy-top in terms of its long-term implications. The winner of this election will determine the future direction of the nation across five very important areas of policy: Taxes, Deficits, Trade, Regulation, and Immigration.

With nearly $4 trillion of tax and spending provisions set to expire, 2025 could be the most important year for tax policy since the creation of the income tax in 1913. These expiring provisions include lower individual rates, a 20% exemption for pass-through entities and higher estate and gift tax exemptions, as well as enhanced Affordable Care Act subsidies to purchase health insurance. The Democratic candidate will likely focus on extending the ACA subsidies and tax cuts for lower-income individuals, while pushing to offset those costs through higher taxes on corporations and high-income individuals. The Republican candidate will seek to extend a wider array of the expiring tax cuts and offset costs through spending cuts, tariffs and scaled-back ACA and green energy subsidies.

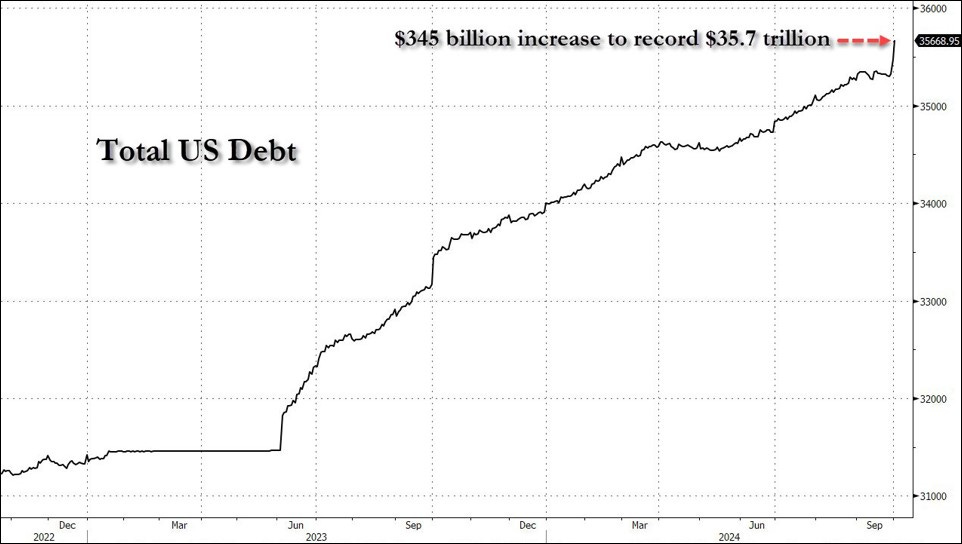

The U.S. budget deficit for fiscal 2024 is expected to be around $2 trillion, or roughly 7% of GDP — an unusually high level for an economy that is not in recession. According to research produced by the Aspen Institute, the budget deficit is projected to climb even higher over the next three decades, reaching 10% of GDP by 2053. The fundamental cause of this steep increase is that, under current law, government spending to fund entitlements is expected to surge as the proportion of the U.S. population over age 65 rises from 17% today, to 22% by 2050. Because interest rates increased in 2022 and 2023, the net interest cost on the deficit is at its highest level in over 25 years. The U.S. Treasury has the tools to mitigate some of the deficit’s effects, but the net interest cost could infringe on other government spending priorities. The debt ceiling expires at the beginning of the next presidential term and Congress will need to raise the debt ceiling at some point in 2025. Both presidential candidates are expected to raise taxes or tariffs to finance an extension of the existing tax code.

Total U.S. government debt just spiked by $345 billion during the month of September to reach $35.7 trillion. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the cost to service this debt in 2025 is expected to exceed $1 trillion for the first time in history, and grow to $1.7 trillion by 2034. While the U.S. Debt-to-GDP ratio is already over 100%, according to research produced by the Aspen Institute, it is projected to reach 180% by 2053. Research published by Reinhart & Rogoff concluded that as a country’s Debt-to-GDP ratio approaches 90%, the GDP multiplier effect of each additional dollar of debt falls to 1.0x. Above 90%, the multiplier turns negative. Case and point, U.S. GDP is estimated to be $28.8 trillion for fiscal 2024. That’s up from $27.4 trillion in fiscal 2023 — an increase of $1.4 trillion Y/Y. Over the same period, the U.S. national debt grew from $33.1 trillion to $35.7 trillion — an increase of $2.6 trillion Y/Y. In other words, it took $1.85 of incremental government debt to produce each $1.00 of incremental GDP over the last year — a negative GDP multiplier effect.

Moreover, after decades of globalization, policymakers of both parties now seek to de-globalize, providing incentives to bolster domestic manufacturing and build out more resilient supply chains. This trend is expected to continue regardless of which party takes the White House. While the current administration has used targeted tariffs to accomplish policy goals (e.g. Mexican steel and aluminum, Chinese EVs), a Republican administration will likely utilize tariffs more broadly to upend supply chains, forcing companies to move faster than they might otherwise. This could lead to supply chain migration away from China and into other countries including India, Mexico, Vietnam, Canada, and perhaps even the good old U.S. of A.

The Republican economic plan centers around deregulation across several critical industries, with a focus on the Financial, Energy and Technology sectors. This will likely result in a streamlining of energy infrastructure projects, expanding liquefied natural gas exports, and increasing fossil fuel usage for domestic electricity. A focus on fewer bank capital buffer restrictions and a broader deregulatory approach toward artificial intelligence is also expected. Should the Democratic ticket emerge victorious, implementing the Inflation Reduction Act, and cleaner energy projects, as well as additional steps toward solidifying antitrust regulation will be the likely focus. A stricter approach to AI regulation may also be in the cards. While far from complete, the table below provides a fairly clear breakdown of where each candidate stands on a number of key economic issues:

Finally, along with the economy, immigration is a key issue for voters in this election. Should the Democratic candidate win the election, many of the current border policies will continue in place. Under a Republican administration, an immediate focus on significantly reducing migration across the southern border is probable. This will have important macroeconomic implications since the Federal Reserve will be focused on the labor supply, and non-native born workers have been filling most of the low wage jobs supporting the U.S. economy.

What is quite clear is that both party’s candidates plan to continue policies that perpetuate the nation’s fiscal budget deficit over the next four years, and lead to an expanded debt burden, which will eventually result in slower economic growth for the country overall (the CBO projects the U.S. national debt to reach $50 trillion by 2034). The path to getting there is the only thing that we see as differentiated. If the Democrats hold the White House, expect the status quo to continue with a few minor changes. By and large, the Democratic platform is disinflationary, but has the potential to slide into deflation, if not kept in check. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), incentives to homebuilders, and higher tax rates are all inherently deflationary. But easing monetary policy may eventually reverse the effects of fiscal policy. The Republican platform is quite the opposite. Expanding and extending tax cuts, expanding tariffs, and a repeal of the IRA are all inherently inflationary. This could eventually result in a further tightening of monetary policy.

The chart above illustrates the three waves of inflation that occurred from the late-1960s through the early-1980s as seen through the lens of the Fed funds rate. While the levels are expected to be less extreme during this cycle — topping first at 5.5% in 2023, then 7.0% by 2027, and finally at 8.0% by 2033, if history repeats itself, then the U.S. economy is in for a rollercoaster ride that will make anything at Six Flags pale by comparison. Today, nominal GDP growth is slowing. The unemployment rate has risen from 3.4% in April 2023 to now 4.1%. Core inflation has come off its boil, but remains sticky, and stubbornly above the Fed’s 2.0% target. These are the green shoots of stagnation. Stagnation can be mistaken for a soft landing, but it is a precondition of stagflation. Stagflation is an economic condition where high inflation, rising unemployment, and slow economic growth occur simultaneously. Stagflation in the 1970s led to two severe back-to-back recessions in the early-1980s.

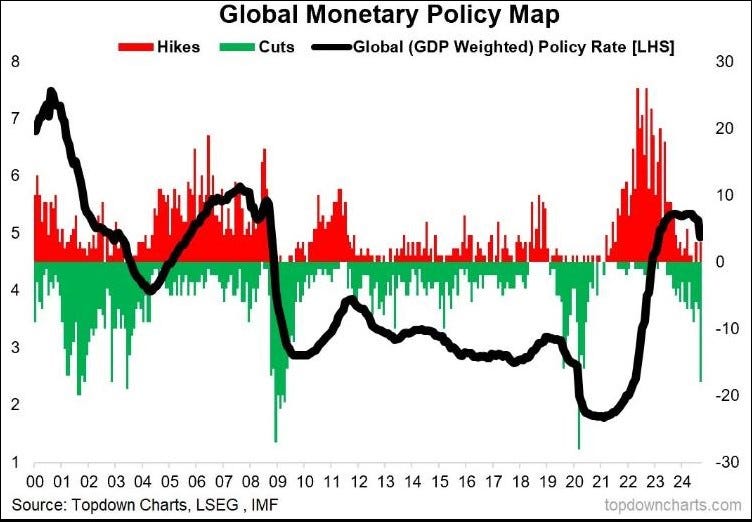

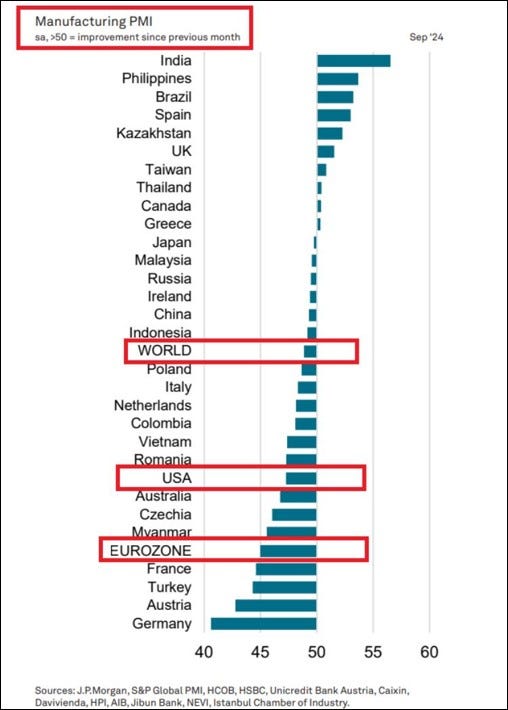

The fiscal and monetary policy response to the distortions of the COVID supply shock have extended the economic cycle. Additional liquidity injections by the Federal Reserve and the Treasury in response to the regional banking crisis added fresh fuel to the fire in March 2023. The emergence of Generative-AI stoked the flames even further, and super-charged the animals spirits of investors, which continue to remain elevated. A global monetary easing cycle is now underway with the largest number of global central banks cutting rates outside of the Tech Wreck, the GFC, or the pandemic collapse. Some see this action as a coordinated unwinding of the previous tightening cycle — a normalization of rates. Maybe that’s correct. But there is also ample evidence to suggest a global slowdown in economic activity is underway, including softening PMI data, labor market deterioration, and slowing GDP growth across Europe, Asia, and the U.S., which suggests there may be other motivations for this abrupt policy shift.

Policymakers tend to have a black and white view of the world that entails a “Go-No Go” approach to their decision making. Therefore, they are either cutting rates preemptively in order to get in front of a potential recession, or they see a clear path to a soft landing, followed by low inflation and accelerating GDP growth. Stagflation is a very underrepresented outcome in most economist’s models. Yet, the longer it takes for a recession to bare its teeth, and the more determined policymakers are to prevent one, the more likely the consequence of the third alternative —stagflation. Moreover, the risk of stagflation increases as the nation’s debt and fiscal deficit expand, which creates a headwind for economic growth by crowding-out private investment, and eventually leads to higher long-term interest rates.

From our lens, in all but a few exceptions, it appears that the world is already experiencing a manufacturing recession. If so, then the risk of further deterioration in the labor market is high — and by extension, the risk to the services component of the global economy is growing. As such, the aggressive and coordinated policy easing by global central banks appears to be targeted toward preempting a recession. The question is: Are they too late? Our inclination at this point is to give central banks the benefit of the doubt. But the reality is that they don’t deserve it. They are most likely behind the curve by at least 115 bps, using the 2-year Treasury yield as our yardstick. If that is the case, then we must assume that central banks will be overtly aggressive at attempting to close that gap. The question then becomes this: What will their efforts achieve?

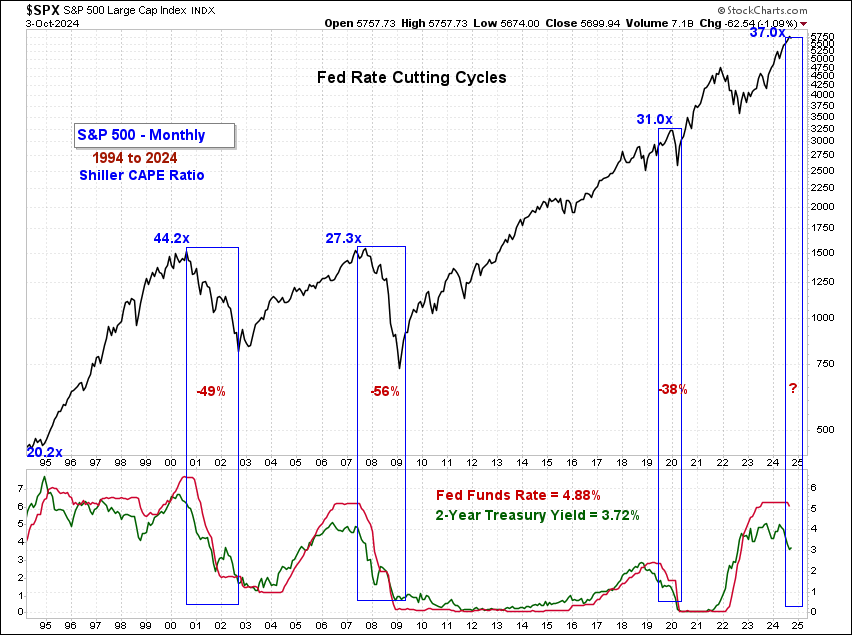

With history as our guide, the lowest probability outcome is a soft landing. In post-WWII history, only one soft landing has ever really been achieved (1994-95) equating to a 7% probability. A recession, on the other hand, was the outcome 93% of the time. Of those 13 recessions since 1945, three were preceded by (1980 and 1981-82), or occurred concomitant with (1973-75) a period of stagflation. Given the current fiscal circumstances — not just in the U.S. but around the globe, coupled with the high level of geopolitical instability, in our opinion, an aggressive and coordinated response by global central banks will likely result in worldwide stagflation — ultimately followed by a severe recession. The bond market is not pricing in a soft landing. We know this because the 10-year minus 2-year Treasury yield curve is un-inverting — just as it always does preceding a recession. Will the stock market too do what it always does?

This is the Fed’s Waterloo. The battle isn’t over, but the’ve already lost the war — they just don’t know it yet. In all likelihood, the U.S. would be better off without central bank intervention. The 8-10% of the working population that lose their jobs generally know how to deal with a recession. They’ll cut-back spending, sell assets, down-size, and work multiple part-time jobs until they get back on their feet. In the long-run, it will be a minor set back. But stagflation will crush everyone — excluding the 1%. The Rothschilds and their modern-day equivalents (Musk, Bezos, Ellison, and the like) will all get their hair messed up a bit, but it won’t hurt. They’ll still fly private. They might cut their travel abroad to once a month. Musk may have to delay his trip to Mars.

Geopolitical Perspectives: China Grove

According to Jerome Mellen, Head of Policy & Operational Support at the United Nations, there are currently 57 ongoing military conflicts on the planet involving 92 countries in total. Mellen suggested that because most of these conflicts relate to unresolved issues dating back many years to decades, the prolonged nature of the disputes transcend the news cycles and are therefore off most people’s radar.

When we spoke with Mellen at a conference in mid-September, it was about a week before Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah was killed in an Israeli airstrike. Even then, the world was still bracing for an attack on Israel from Iran in retaliation for the July 3rd death of another senior Hezbollah commander by the name of Muhammad Nimah Nasser — also the victim of a well-orchestrated Israeli airstrike.

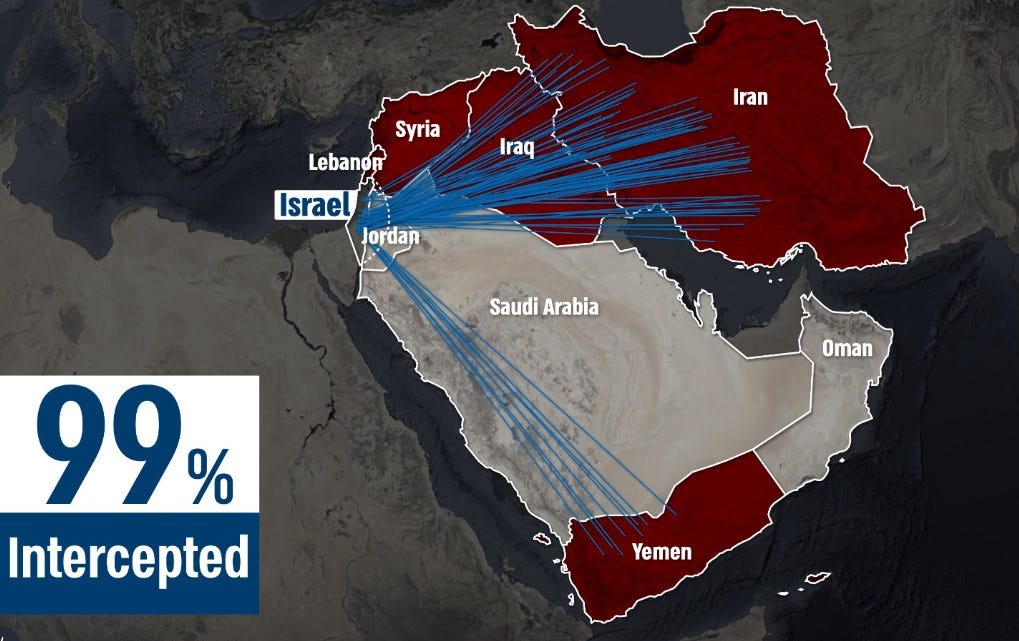

On October 1st, Iran launched approximately 180 ballistic missiles at military and civilian targets in Israel, including the populous coastal cities of Haifa and Tel Aviv. Israeli air defences — know as the “Iron Dome,” along with help from two U.S. guided-missile destroyers — the USS Bulkeley and the USS Cole — were successful in intercepting and destroying 99% of the incoming missiles.

Iran’s latest attack on Israel is a testament to how quickly things can change. Now the world is bracing for the opposite. How might Israel respond to Iran’s missile attack? From nuclear facilities to oil field infrastructure, all options appear to be on the table as Israel prepares to launch a retaliatory strike on strategic Iranian assets. Iranian naval base facilities at the port city of Bandar-e Bushehr along with naval assets of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps are also considered potential targets for Israel according to several military strategists. But if past is prologue, Tel Aviv may also continue the string of targeted assassinations by going after Iranian leaders as it did with Hezbollah. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has since been taken to a secure location inside Iran amid heightened security according to a Reuters report.

Two thousand miles to the North of Jerusalem, the Russian war against Ukraine rages on. There is only one way that this war ends — Russia must stop fighting. This conflict represents one of the most successful examples of asymmetric warfare in modern history. Ukrainian sea drones at a cost of just $220K each have sunk or critically damaged more than two dozen Russian warships in the Black Sea. The downed Russian cruiser Moskva alone had a replacement value of at least $750M. All in, the estimated replacement value of lost Russian warships exceeds $5 billion. Add in weapons, fuel and lost strategic value, and the number is easily double that figure. To avoid further Ukrainian stikes, Russian ships have been forced to leave their former headquarters in the occupied Crimean port of Sevastopol, and move farther east. They no longer patrol the Ukrainian coast, nor can they stop Ukrainian cargo ships from carrying grain and other goods to world markets. Ukraine, a country without a navy, defeated Russia’s Black Sea fleet.

Putin’s failure in Ukraine appears to have lessened the risk of a Chinese incursion into Taiwan. Xi cannot afford to take the risk. If the PLA were to become bogged-down in a prolonged military conflict in Taiwan the way Russia has in Ukraine, it could undermine his power and potentially lead to his ouster. At this point Xi is content simply to pretend that he is a threat to Taiwan. He is well-aware that if the U.S. can equip Ukraine with such asymmetrically effective weaponry, it can — and likely has — already done the same for Taiwan. Importantly, Xi has now sent an important signal to the West. He has fired a bazooka of a different variety. One that he aimed at his own economy. After four years of flagging economic growth, Xi hollered, “Uncle.” He will now focus his attention on reviving the Chinese economic machine.

On September 27th, less than 10-days after the Fed’s surprise 50 bps rate cut decision, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) cut their reserve requirement ratio for lenders by 50 bps, and announced a series of fiscal support measures designed to shore-up their struggling equity and real estate markets, with plans to issue 2 trillion yuan (equal to approximately $285 billion) in special sovereign bonds. This will immediately release about 1 trillion yuan in liquidity into the banking system. The action suggests that Chinese authorities in Beijing have reached their pain threshold following years of slowing GDP growth. The scale of the policy support is the largest since 2015 and appears substantial enough to boost the growth rate of the second largest economy in the world back to Beijing’s stated 5% annual target.

There can be no doubt that the markets applauded the Chinese central bank’s action. Following the announcement, the Hang Seng index saw the largest breadth thrust in its history. On October 1st, CNBC interviewed billionaire hedge fund titan David Tepper, who called for an “everything” rally in China. When asked by the show’s anchors what stocks he was buying in China, Tepper could hardly contain himself. Before the question was even complete, the word “everything” was repeated by Tepper again and again. When asked why he thought this stimulus action would work when others failed, Tepper highlighted the fact that the PBoC stated that they would provide additional policy support if necessary, “I have to take them at their word.” He also focused on the fact that the PBoC was creating swap lines so that Chinese companies could borrow money from the government in order to facilitate stock buybacks, “The government is giving companies money to buy their own stocks.”

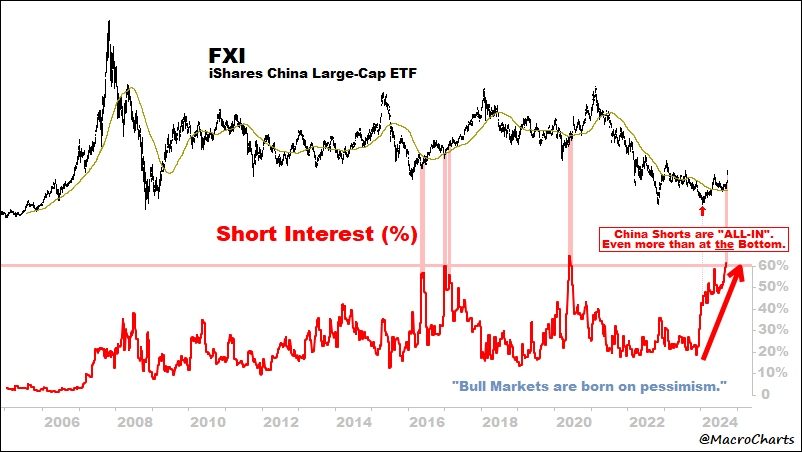

The knee jerk reaction to this announcement is not surprising given the near-record short interest evident in Chinese equities here in the U.S. As John Templeton once famously said, “Bull markets are born on pessimism, grow on skepticism, mature on optimism, and die on euphoria.” But there is another reason to consider Chinese stocks today — they’re just plain cheap! An analysis of global equity market valuations by region reveals that Chinese equity valuations are by far the cheapest in the world, where as U.S. equity market valuations are by far the most expensive. Not only are Chinese stocks cheap relative to U.S. stocks, they are cheap relative to foreign developed market and emerging market equities at large. Moreover, Chinese stocks are cheap relative to their own 25-year historical valuation range and currently trade below their 25-year average P/E valuation on FTM estimated earnings.

On the flip side, another billionaire hedge fund titan by the name of Stan Druckenmiller isn’t buying it. Even if Chinese stocks go up a lot, he just doesn’t trust the Chinese leadership, and is quite comfortable holding gold and going short U.S. T-bonds as a way to bet against the U.S. dollar and hedge inflation. Meanwhile, the shares of the iShares China Large-Cap ETF (FXI), which we actually recommended to our paid subscribers on September 25th — before the big announcement out of Beijing, appear to have resolved above a multi-year classic patterned base formation of the “Double Bottom” variety. The bullish inflection above $30, if sustained, projects a measured move to approximately $40 [($30 - $20) + $30 = $40]. But, more likely, FXI will retrace a Fibonacci 61.8% of the decline off the February 2021 high before correcting the latest advance. We think that a modest pull-back to $32 could precede the next leg higher. If so, then the set-up would present a 30% profit potential. An initial stop-loss provision set at $29 would limit downside risk to 9.3% of capital deployed, establishing an attractive 3:1 positive risk skew.

There is another quote that is attributed to Nathan Rothschild, where some evidence actually exists to support the claim. It seems apropos with respect to China today:

“Fortunes are made by buying low and selling too soon.”

Market Analysis & Outlook: All Apologies

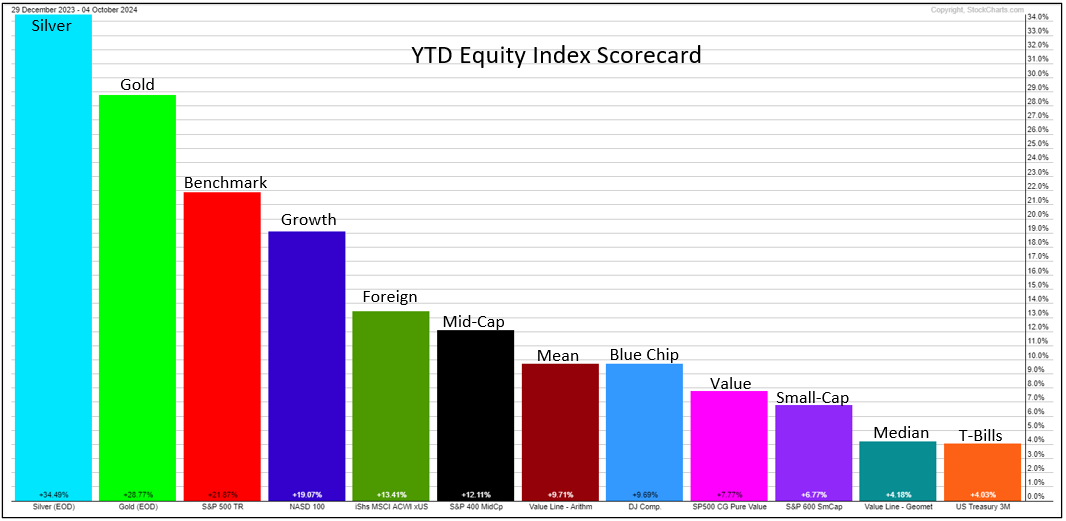

We’ve been wrong to maintain an overly cautious view toward U.S. equities this year, but we’ve been right to be aggressively bullish gold. Heading into 2024, we called gold our top actionable trade idea for the year. So far, it has not disappointed. Most investment strategists who profess to be bullish on stocks hold only a modest “overweight” relative to their 60/40 stock-bond benchmarks. This overweight typically amounts to pushing their equity allocation to 65% or 70% of a balanced portfolio. And while some investment strategists have recently added gold to their asset allocation, when pressed about how much gold to hold, few will advocate holding more than 5%, while the vast majority draw the line at 2%. We, on the other hand, have been boldly recommending a 10-20% allocation to gold since January, and added a 5% allocation to silver in April. Both gold and silver have radically outperformed the popular stock averages YTD — gaining +29% and +34%, respectively. Meanwhile, the median U.S. stock’s performance is a mere +4.2% according to Value Line — in-line with T-Bills.

While we regret being underweight equities during such a torrid rally in the S&P 500 this year, we would rather be underweight stocks wishing we were overweight, than overweight stocks wishing we were underweight. Indeed, there are still plenty of reasons for concern — least of which is valuation. But valuation, nevertheless, remains concerning. As of quarter-end, the Total U.S. Market Cap-to-GDP ratio