Please enjoy the free portion of this monthly newsletter with our compliments. To get full access, you might want to consider an upgrade to paid for as little as $12.50/month. As an added bonus, paid subscribers also receive our weekly ALPHA INSIGHTS: Idea Generator Lab publication, which details our top actionable trade idea and provides updated market analysis every Wednesday, as well as other random perks, including periodic ALPHA INSIGHTS: Interim Bulletin reports and quarterly video content.

Executive Summary

Shadow Banking Crisis: The Domino Effect

Economy & Interest Rates: A Contrarian View

Geopolitical Perspectives: Exit the Dragon

Market Analysis & Outlook: Did Santa Claus Come Early this Year?

Conclusions & Positioning: Follow the Yellow Brick Road

The Domino Effect

Zhongzhi Enterprise Group — perhaps the most important company that you’ve never heard of. What makes this company so important you ask? Well, it’s not because of its technology. Nor is it because of its growth rate. And it’s certainly not because of its profitability. The reason that Zhongzhi is so important today is because it may soon become infamous for being the epicenter of the next global financial crisis.

Zhongzhi controls nearly a dozen asset and wealth management firms. The Beijing-based company is considered part of China’s $3 trillion “shadow banking” industry, a sector that forms an important source of finance in the country. The term usually refers to financing activity that takes place outside the formal banking system, either by banks through off-balance-sheet activities, or by non-bank financial institutions, such as trust firms.

Last week, in a letter to its investors, Zhongzhi revealed that it has a “huge debt,” and that it “cannot pay all of its bills.” It pegged its total liabilities at 460 billion yuan ($64 billion), against assets of 200 billion yuan ($28 billion). Beijing police began a probe into the wealth management units of Zhongzhi last weekend. According to a statement posted on November 25th, police suspect Zhongzhi of “illegal crimes” (apparently some crimes in China are not illegal), and have enforced “mandatory criminal measures” against a number of suspects, including one surnamed Xie.

The founder of the group, Xie Zhikun, died of a heart attack in December 2021, but his nephews hold key posts in the company, according to Chinese state media. “Liquidity is exhausted, and asset impairment is serious,” Zhongzhi said in the letter, which was cited by Chinese state-owned news outlets. Zhongzhi apologized for its financial woes, and said that since the death of its founder in 2021, and the subsequent resignations of senior executives, it had struggled with “ineffective” internal management.

Concern about Zhongzhi’s finances were first triggered in August when a trust it partially owns — Zhongrong International Trust — missed payments to individual and corporate investors in the amount of 110 million yuan. A major reason behind the company’s financial woes is its strong links with China’s real estate sector. Zhongrong, which managed 87 billion yuan worth of funds for corporate clients and wealthy individuals, had invested heavily in real estate, according to its annual report from last year. The missed payments underscore how China’s prolonged property downturn may be spilling over into its financial industry.

Across the Atlantic, Austrian real estate tycoon Rene Benko’s Signa Holdings declared it was insolvent on Wednesday, making it the biggest casualty so far of Europe’s property market crash. Famous for its ownership of the iconic Chrysler Building in New York, along with several high-end retail properties across Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, Signa has amassed unsecured debts amounting to over $5 billion euros.

The venerable Swiss Private Bank Julius Baer Group Ltd, saw its stock plunge 20% to a three-year low last week after it revealed exposure of more than 600 million Swiss francs to the Signa fiasco. Julius Baer admits that they could experience a complete loss on the loans to Singa. If so, such a loss would put “significant” pressure on their CET1 capital ratio, potentially impairing the bank’s ability to return capital to shareholders through dividends and stock buybacks. The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority has not taken action yet, but already had the bank on its watchlist for past improprieties.

After watching the Federal Reserve pump $5 trillion into the U.S. banking system following the COVID collapse, most observers don’t see the problem with a $36 billion loss on some upside down real estate trust in China, or a $5 billion loss from a shopping center developer in Austria. Those numbers are chump change — a rounding error in the grand scheme of things. But, lest we forget, it was just 25-years ago that another private partnership called Long-Term Capital Management required a bailout from the Federal Reserve in the amount of a mere $3.625 billion in order to avoid a potential chain reaction across the firm’s counterparties — a domino effect — which many at the time believed could result in a total collapse of the global financial system.

The point is that it’s not so much the size of the initial loss that is important, but it’s who is on the other side of the losing trade that really matters, and the extent to which the aggregate consequences of that loss can compound. Take Julius Baer for example. Their 600 million Swiss franc exposure might sound like a seemingly small number compared to Signa’s $5 billion in total unsecured liabilities. To JP Morgan it would be, but to a much smaller counterparty such as Julius Baer, a loss of that size poses serious consequences. Once the dominos begin to tumble, the potential collateral damage is unpredictable. In a best case scenario, the bank delays its stock buyback plan. In a worst case scenario, the bank could become the next Credit Suisse.

Importantly, the underlying problem of impaired loan collateral is not exclusive to China or Europe. As we’ve discussed in several past issues, U.S. commercial real estate (CRE) asset valuations have been clobbered over the past two years, leading to defaults on numerous trophy properties in New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and numerous other markets. Indeed, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) just released its quarterly assessment of past-due and noncurrent CRE loans for 3Q23. It reached the highest level of the past decade. With an estimated $2 trillion of CRE debt maturing over the next two years, rising caution among private lenders will worsen the paucity of liquidity for property owners who have no real exit option. If property valuations continue to drop on worsening CRE fundamentals, borrowers may find that not only are private lenders refinancing loans at rates up to 500 bps higher than their prior terms, but with significantly lower leverage ratios.

A Contrarian View

The late, great value investor Charlie Munger — of Berkshire Hathaway fame, who recently departed this world just shy of his 100th birthday, had a lot to say over the course of his career about the foolish excesses that could find their into the prices of common stocks. He once said that stocks were priced “partly like bonds, based on roughly rational projections of use value in producing future cash. But they are also valued partly like Rembrandt paintings, purchased mostly because their prices have gone up — so far.” It seems to us that Munger’s logic applies equally, if not doubly, to the CRE market based upon the cap rates that were paid for Class A office and retail properties prior to the pandemic shutdown.

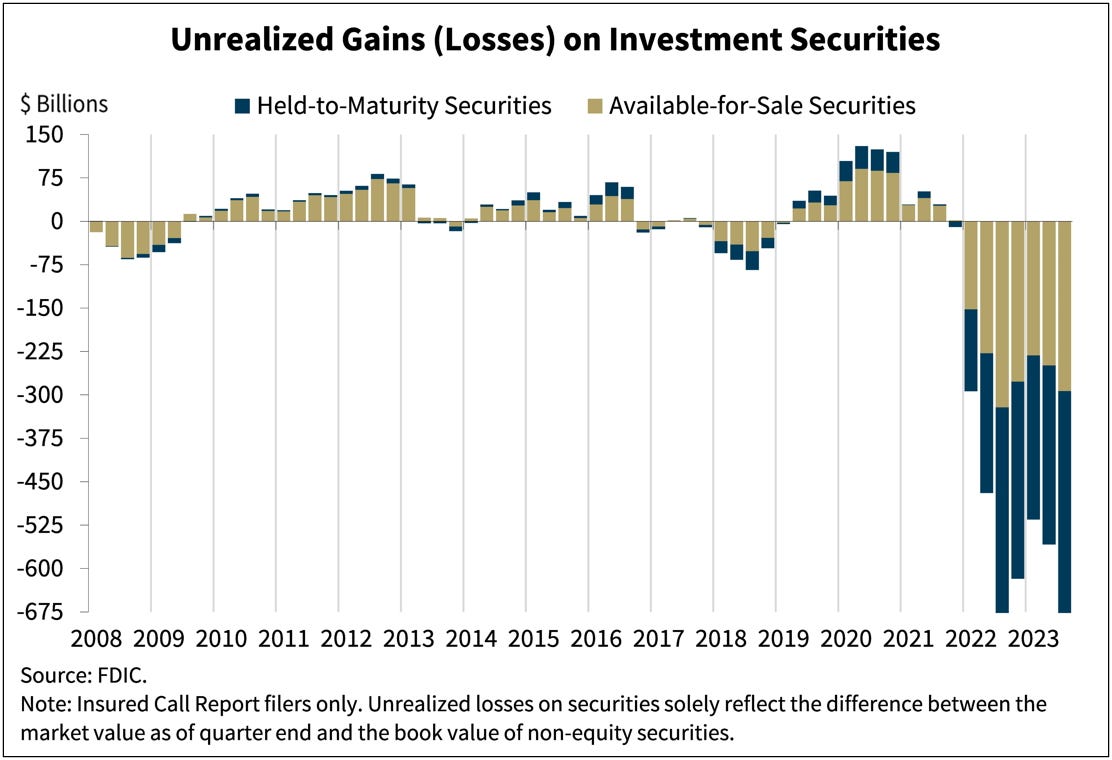

But refinancing CRE loans isn’t the banking industry’s only problem. The level of unrealized losses on investment securities held on bank balance sheets industry-wide grew by 22.5% sequentially to $683.9 billion during the third quarter. These losses compound the negative impact on liquidity that collapsing bank deposits have had on credit availability over the past year. Of course, the third quarter ended on September 30th, before the 175 bps back-up in 10-year Treasury yields really crushed bond prices. The market has since pulled-back from the October peak in rates, and closed the month of November some 25 bps below where the September quarter mark was taken. But our work suggests that the rally in bond yields has not yet reached its full potential. The chart below illustrates a new multi-year bull market in bond yields.