Please enjoy the free portion of this monthly investment newsletter with our compliments. To get full access, you may want to consider an upgrade to paid for as little as $15/month. As an added bonus, paid subscribers also receive our weekly ALPHA INSIGHTS: Idea Generator Lab report, an institutional publication that provides updated market analysis and details our top actionable ETF idea every Wednesday. Thanks for your interest in our work!

Executive Summary

Unsinkable?

Macro Perspectives: Recession Specials on Deck

Geopolitics: Amerika

Market Analysis & Outlook: Iceberg Right Ahead

Conclusions & Positioning: Man the Life Boats

Unsinkable?

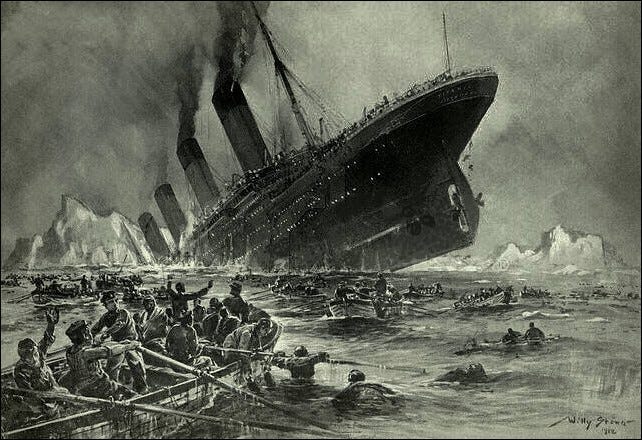

On the night of April 14th, 1912, during her maiden voyage, the Olympic-class ocean liner RMS Titanic hit an iceberg, and sank two hours and forty minutes later. The sinking resulted in the deaths of 1,517 people, ranking it as one of the deadliest peacetime disasters in maritime history. The Titanic was a White Star Line ocean liner, built at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, Ireland. Construction of the Titanic, funded by the American financier, J.P. Morgan and his International Mercantile Marine Co., began in March 1909. At the time of her launching exactly three years later, Titanic was the largest passenger steamship in the world, and sported some of the most advanced technology then available. Prior to that fateful eve, she was popularly believed to be “unsinkable.”

Ironically, the human condition that preceded the tragedy befalling Titanic, is in many ways similar to that which has paved the way for every financial disaster that investors have endured over the entire history of the stock market. It is hubris — a dangerous form of overconfidence, which leads to excessive risk taking and irrational decision making. Indeed, following the all-time record high that the S&P 500 achieved on February 19th, it was unimaginable to most market watchers that just seven weeks later, the benchmark index would be plumbing the lows of a 21.4% peak-to-trough decline.

Prior to the sell-off, Treasury officials and Fed governors had regularly praised the U.S. economy for its flexibility and global competitive position. Indeed, on the very day of the market’s high, while speaking to an audience at the Future Investment Initiative Institute in Miami, President Trump himself said, “I think the stock market is going to be great. In other words, we will rapidly grow our economy by dramatically shrinking the federal government.” Terms like “strong fundamentals,” “earnings growth acceleration,” and “low inflation” were regularly bandied about in the financial media and could be heard echoing in the background at cocktail parties everywhere. Yet, like the Titanic, despite state-of-the-art financial infrastructure and throngs of bullish pundits, the stock market proved anything but unsinkable. It was the third such 20%-plus decline in the past five-and-a-half years.

To be sure, Titanic was state of the art as well. She was 269 meters long and 28 meters wide, with a gross register tonnage of 46,328 tons and a height from the water line to the boat deck of 18 meters. She contained two reciprocating four-cylinder, triple-expansion, inverted steam engines and one low-pressure Parsons turbine, which powered three propellers. There were 29 boilers fired by 159 coal burning furnaces that made possible a top speed of 23 knots. Three of the four 19 meter tall funnels were functional; the fourth, which served only as a vent, was added to make the ship look more impressive. She had capacity for 3,547 passengers and crew. At the time, Titanic surpassed all rivals in luxury and opulence.

She offered an on-board swimming pool, a gymnasium, a Turkish bath, libraries in both the first and second-class, and a squash court. First-class common rooms were adorned with elaborate wood paneling, expensive furniture and other decorations. The ship incorporated technologically advanced features for the period. She had an extensive electrical subsystem with steam-powered generators and ship-wide electrical wiring feeding electric lights. She also boasted two Marconi radios, including a powerful 1,500-watt set manned by operators who worked in shifts, allowing constant contact and the transmission of many passenger messages.

Titanic began her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, bound for New York City, on April 10th, 1912, under the command of Captain Edward J. Smith. Some of the most prominent people in the world were traveling in first–class. These included millionaire John Jacob Astor; industrialist Benjamin Guggenheim; Macy’s owner Isidor Straus; Denver millionairess Margaret “Molly” Brown; Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon; George Elkins Widener; John Borland Thayer; journalist William Thomas Stead; the Countess of Rothes; U.S. presidential aide Archibald Butt; author and socialite Helen Churchill Candee; author Jacques Futrelle; Broadway producers Henry and Irene Harris; and silent film actress Dorothy Gibson, just to name a few. Also traveling in first–class were White Star Line’s managing director J. Bruce Ismay who came up with the idea for Titanic, and the ship’s builder Thomas Andrews, who was on board to observe any problems and assess the general performance of the new ship.

While visiting Belfast, Ireland in May, we had the opportunity to spend several hours at the Titanic Museum. It is both a monument to the city’s maritime heritage as well as to the 1,517 soles that perished in the Atlantic more than 113 years ago. The Titanic Experience itself includes several vignettes ranging from the boomtown beginnings of Belfast, to a theme park-like “Shipyard” ride that explores the construction of Titanic at the Harland and Wolff shipyard. Then the self-guided tour takes a somber turn toward the events that led to the sinking of the Titanic and the tragic loss of life that attended it, the aftermath, the myths and legends that followed, and of course, the discovery of the wreck.

But, perhaps the most powerful part of the tour came with the revelation of various old newspaper clippings detailing the accounts and statements of some of the survivors. One such newspaper clipping that made a particularly strong impression on us was printed in the Cleveland Plain Dealer on April 19th, 1912, in which first class passenger Caroline Bonnell recounted her experience. The following quote sums up the attitude of hubris among some of the most prominent people on the Titanic:

“We were asleep in our berths when the Titanic crashed into the iceberg,” Miss Caroline Bonnell said. “We immediately rushed on deck, only stopping to throw coats over our nightclothes. We could see the crowds of passengers falling down the stairs, while the officers sought to reassure them of their safety. Major Butt and Colonel Astor stood by the lifeboats bravely and helped the women. They did not think the boat was going to sink.”

~ Titanic survivor, Cleveland Plain Dealer - April 19, 1912

The Anatomy of a Disaster

According to David G. Brown’s, The Last Log of the Titanic, on the night of Sunday, April 14th, the temperature had dropped to near freezing and the ocean was calm. The moon was not visible and the sky was clear. Captain Smith, in response to iceberg warnings received via wireless over the preceding few days, altered the Titanic’s course slightly to the south. That Sunday at 1:45 PM, a message from the steamer Amerika warned that large icebergs lay in the Titanic’s path, but as Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, the Marconi wireless radio operators, were employed by Marconi and paid only to relay messages to and from the passengers, they were not focused on relaying such “non-essential” ice messages to the bridge. Later that evening, another report of numerous large icebergs, this time from the Mesaba, also failed to reach the bridge.

At 11:40 PM while sailing south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, lookouts Fredrick Fleet and Reginald Lee spotted a large iceberg directly ahead of the ship. Fleet sounded the ship’s bell three times and telephoned the bridge exclaiming, “Iceberg, right ahead!” First Officer Murdoch ordered an abrupt turn to starboard and the engines to be stopped. A collision was inevitable and the iceberg brushed the ship’s starboard side, buckling the hull in several places and popping out rivets below the waterline over a length of 90 meters. As seawater filled the forward compartments, the watertight doors shut. However, while the ship could stay afloat with four flooded compartments, five were filling with water. The five water-filled compartments weighed down the ship so that the tops of the forward watertight bulkheads fell below the ship’s waterline, allowing water to pour into additional compartments. Captain Smith, alerted by the jolt of the impact, arrived on the bridge and ordered a full stop. Shortly after midnight on April 15th, following an inspection by the ship’s officers and Thomas Andrews, the lifeboats were ordered to be readied and a distress call was sent out.

The first lifeboat, boat 7, launched at 1:27 AM on the starboard side with 28 people on board out of a capacity of 65. Boat 5 was launched two to three minutes later. The Titanic carried 20 lifeboats with a total capacity of 1,178 persons. While not enough to hold all of the passengers and crew, the Titanic carried more boats than was required by the British Board of Trade Regulations. At the time, the number of lifeboats required was determined by a ship’s gross register tonnage, rather than her human capacity. Wireless operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride were ordered to send out CQD, the international distress signal. Several ships responded, including Mount Temple, Frankfurt and Titanic’s sister ship, Olympic, but none was close enough to make it in time. The closest ship to respond was Cunard Line’s RMS Carpathia 58 miles away, which arrived in about four hours — too late to rescue all of Titanic’s passengers. The only land-based location that received the distress call from Titanic was a wireless station at Cape Race, Newfoundland.

From the bridge, the lights of a nearby ship could be seen off the port side. Not responding to wireless, Fourth Officer Boxhall and Quartermaster Rowe attempted signaling the ship with a Morse lamp and later with distress rockets, but the ship never appeared to respond. The SS Californian, which was nearby and stopped for the night because of ice, also saw lights in the distance. The Californian’s wireless was turned off, and the wireless operator had gone to bed for the night. Just before he went to bed at around 11:00 PM the Californian’s radio operator attempted to warn the Titanic that there was ice ahead, but he was cut off by Jack Phillips, who snapped, “Shut up, shut up, I am busy; I am working Cape Race”. When the Californian’s officers first saw the ship, they tried signaling her with their Morse lamp, but also never appeared to receive a response. Later, they noticed the Titanic’s distress signals over the lights and informed Captain Stanley Lord. Even though there was much discussion about the mysterious ship, which to the officers on duty appeared to be moving away, the Californian did not wake her wireless operator until morning.

The Titanic showed no outward signs of being in imminent danger, and its passengers were reluctant to leave the apparent safety of the ship to board small lifeboats. As a result, most of the boats were launched partially empty; one boat meant to hold 40 people left the Titanic with only 12 people on board it. With “Women and children first” the imperative for loading lifeboats, Second Officer Lightoller, who was loading boats on the port side, allowed men to board only if oarsmen were needed, even if there was room. First Officer Murdoch, who was loading boats on the starboard side, let men on board if women were absent. As the ship’s list increased, passengers started to become nervous, and some lifeboats began leaving fully loaded. By 2:05 AM, the entire bow was under water, and all the lifeboats had been launched, but two.

Around 2:10 AM, according to eye-witness accounts, the stern rose out of the water exposing the propellers, and by 2:17 the waterline had reached the boat deck. The last two lifeboats floated off the deck, one upside down, the other half filled with water. Shortly afterwards, the forward funnel collapsed, crushing part of the bridge and people in the water. On deck, people were scrambling towards the stern or jumping overboard in hopes of reaching a lifeboat. The ship’s stern slowly rose into the air, and everything unsecured crashed towards the water. While the stern rose, the electrical system finally failed and the lights went out. Shortly afterwards, the stress on the hull caused Titanic to break apart between the last two funnels, and the bow went completely under. The stern righted itself slightly and then rose vertically. After a few moments, at 2:20 AM, this too sank into the ocean.

Contrasts with an Impending Financial Crisis

The shear scale and engineering marvel that was Titanic created the illusion that the ship was infallible, and thus, the risks that would normally accompany a Trans-Atlantic voyage by sea were apparently disregarded by both passengers and crew. Similarly, today’s fascination with AI and the pace of advances in the field have left investors with the impression that the opportunity cost of missing out on the AI boom is much higher than the risk of it not living up to expectations. The past experience of observing the government rescue of the stock market time and again since the Great Financial Crisis, has desensitized investors to the risks of investing in equities. Access to information and low-cost, lightening-fast trade execution via hand-held devices has leveled the playing field between professional and non-professional investors. Yet, while non-professional investors may now have access to the same tools as professionals, most lack the wisdom, education, and experience of professionals, creating a false sense of confidence among that cohort. In both cases, it is complexity that conceals the reality of the situation.

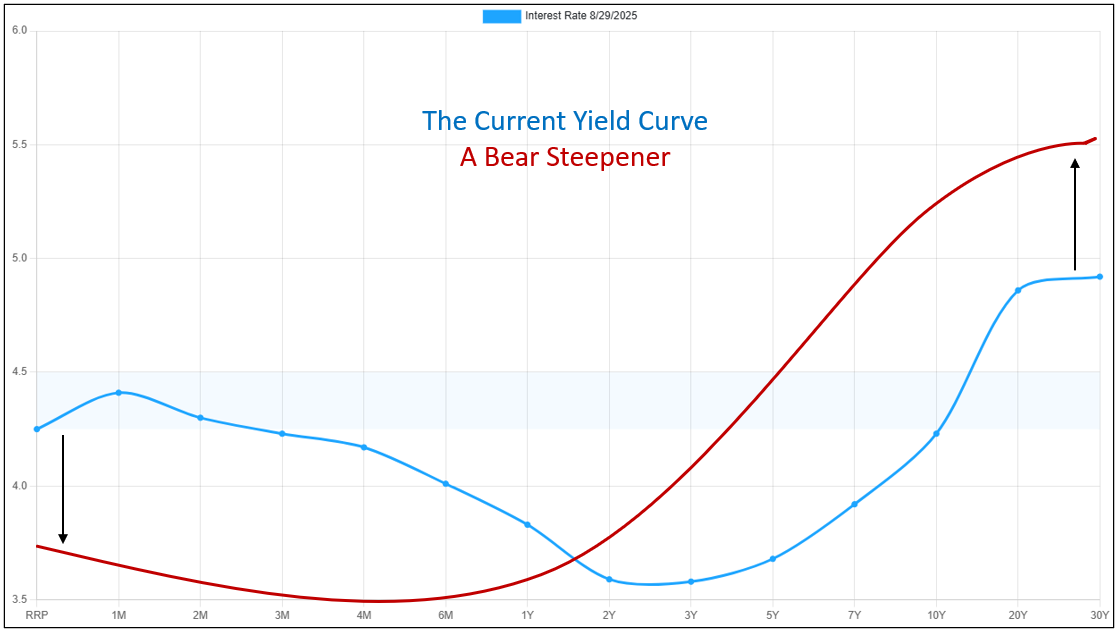

For Captain Smith, it was overconfidence in his training and experience that created the misapprehension. Titanic’s advanced technology gave her the advantage of speed, but it was that advantage that also proved to be her Achilles’ heel. Her mass and displacement made her much less responsive at the helm, and she had a small rudder for a ship of her size. It was later determined that by holding speed at full ahead, the thrust of the center prop would have magnified the rudder’s response. Every evasive action that Smith’s crew knew from their past experience at sea was thus wrong. Likewise, economists on Wall Street today depend too much on their understanding of the monetarist and Keynesian economic philosophies, which advocate for active government intervention through monetary and fiscal policy. The assumption that the government has the unlimited power to print money, spend, and cut taxes, without any negative consequences is inherently flawed. As discussed in previous issues, research by Reinhart and Rogoff concluded that as a country’s debt-to-GDP exceeds 90%, increased borrowing actually decreases economic growth. Moreover, cutting the Fed’s policy rate to stimulate growth during periods of elevated inflation, whether perceived or realized, can cause long-term rates to rise aggressively, resulting in a more amplified steepening of the yield curve — the dreaded “bear steepener.”

As with Titanic, the modern global financial system also suffers from similar shortcomings in the areas of regulatory oversight. For example, the lack of adequate life boat capacity and muster drills, coupled with poor ship-to-ship communications protocols led to a doom spiral for Titanic. Today, financial regulators are more concerned with democratizing access to the riskiest assets (cryptocurrency, private equity, and other exotic alternatives), than they are in debating why the guard rails were installed in the first place. Heretofore, access to those assets was reserved for qualified institutional and accredited high net-worth investors, because they had the financial wherewithal to absorb losses and the education and professional resources to do the due diligence necessary to fully-understand the applicable risk/reward proposition. The average retail investor does not. In short, those guardrails exist for the investor’s protection.

The argument in favor of opening up access to private equity investments to retail investors is so that they too can capitalize on the additional diversification benefits of lower volatility and historically superior long-term returns (debatable). Yet, every prospectus that we have ever read, states clearly that “past performance is no guarantee of future results.” As for the benefits of additional diversification, the only reason that these assets are lower in volatility is because they are not marked-to-market every day like public market securities. And when they are marked-to-market, the mark is often of a dubious nature. Moreover, the descriptive term “private equity” only serves to reduce the stigma associated with the term originally used to describe the asset class, “leveraged-buyout.” Perhaps an more apt descriptive term would be “leveraged equity.” It would certainly explain the reason why the returns are higher with much greater transparency. If the GFC taught us anything, it is that low volatility in the capital markets leads to complacency among both investors and regulators alike. In our opinion, the democratization of such alternative assets serves no purpose other than to create a cohort of greater fools.

Importantly, the actions and inactions of leadership in the face of a crisis are always critical to determining the outcome, and politics always play a role. For Titanic, it was the lust for public notoriety and pride that led J. Bruce Ismay to insist that Captain Smith push the ship to its limits, so that he could win favor of his superiors at White Star Lines. For financial markets today, it is the bizarre lust for power and control that has prompted the current President of the United States to use his cult of personality to micro-manage virtually all aspects of government, business, and society, from his attempts to influence monetary policy, radically change the basic framework of global trade, enact and enforce invasive new immigration policies, ignore or circumvent court rulings, usurp authority from state and local governments through the deployment of Federal troops, and nationalize private enterprises, to his self-aggrandizing behavior and the surrounding of himself with a cadre of political sycophants to shower him with endless praise. All of this serves to undermine the public’s confidence in established institutions, systems, and the rule of law and rights governed by the Constitution of the United States. And all of this is occurring at a time when valuations and expectations have never been higher.

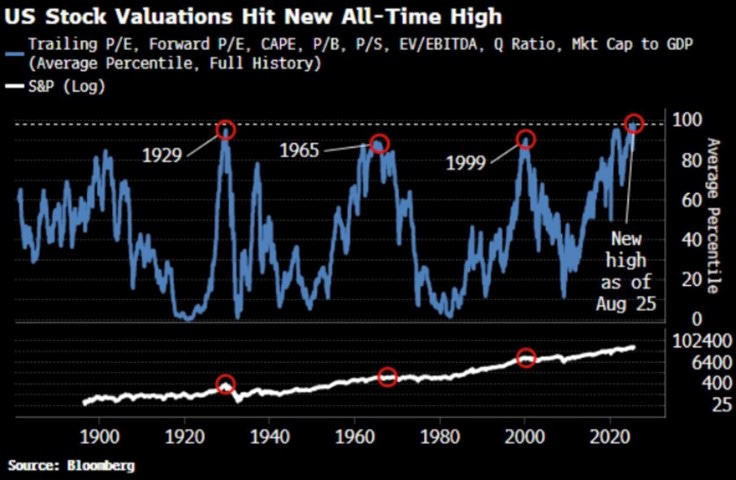

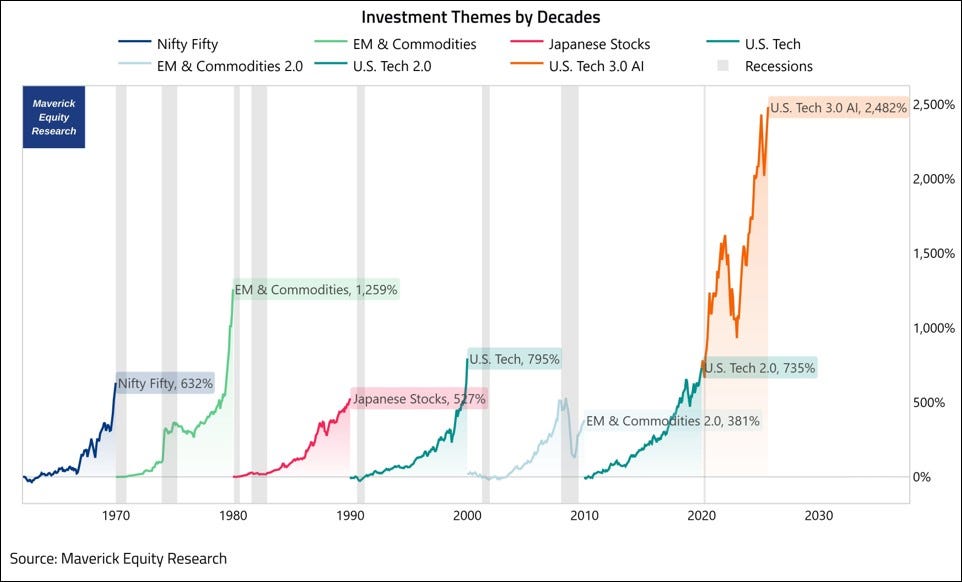

For months we’ve presented data-set after data-set illustrating that the S&P 500 index currently trades at valuation levels that are heretofore unprecedented. The chart above illustrates the aggregation of many of these data-sets going back to the late-19th century. As of August 25th, based upon the average percentile of the TTM P/E ratio, the FTM P/E ratio, the CAPE ratio, the P/B ratio, the P/S ratio, the Market Cap/GDP ratio, and Tobin’s Q, the valuation of the S&P 500 index has reached an all-time record high — surpassing the Dot-Com bubble peak in 1999, the post-WWII recovery peak in 1965, and the Roaring 20’s peak in 1929. Will this period be remembered as the AI Bubble peak of 2025?

Harris (Kuppy) Kupperman, Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Praetorian Capital Management, believes the answer to that question is, yes. In a recent post on his firm’s blog entitled, Global Crossing is Reborn, Kuppy berates himself for being an “old school” investor who still believes that things like cash flow and return on capital matter. He describes these factors as his north star, and admits that he often misses new trends because he refuses to pay up for profitless prosperity. He reflects that cash flow is king, ROIC is queen, and everything else is just stock promotion. His blog caught our attention because we made a similar argument last month in Issue #48, and in fact, we even made a reference to Global Crossing. Next, Kuppy writes:

“I’ve watched as AI went from an interesting parlor trick for making memes, to something that’s increasingly integrated into my daily workflow. I use it a lot and get huge value from it. I am not here to belittle AI, it’s the future, and I recognize that we’re just scratching the surface in terms of what it can do. I recognize all of this. I also recognize massive capital misallocation when I see it. I recognize an insanity bubble, and I recognize hubris.”

Clearly, we are of the same mindset on this point as well. As we wrote last month, we are not forensic accountants. Indeed, we made straight “B’s” in financial accounting (although we still take some satisfaction in the fact that we earned an “A” in cost accounting — a feat that we must attribute to a well-written book entitled, The Goal). That being said, like James Chanos, Kuppy was a straight “A” student in accounting. Below we’ve reproduced some of the key highlights from Global Crossing is Reborn, especially as it pertains to the obvious mispricing of the AI trade at large. Kuppy wrote:

“I’m going to use a bunch of numbers here that I believe to be directionally correct, as I’ve spoken with industry players who have somewhat confirmed these numbers.

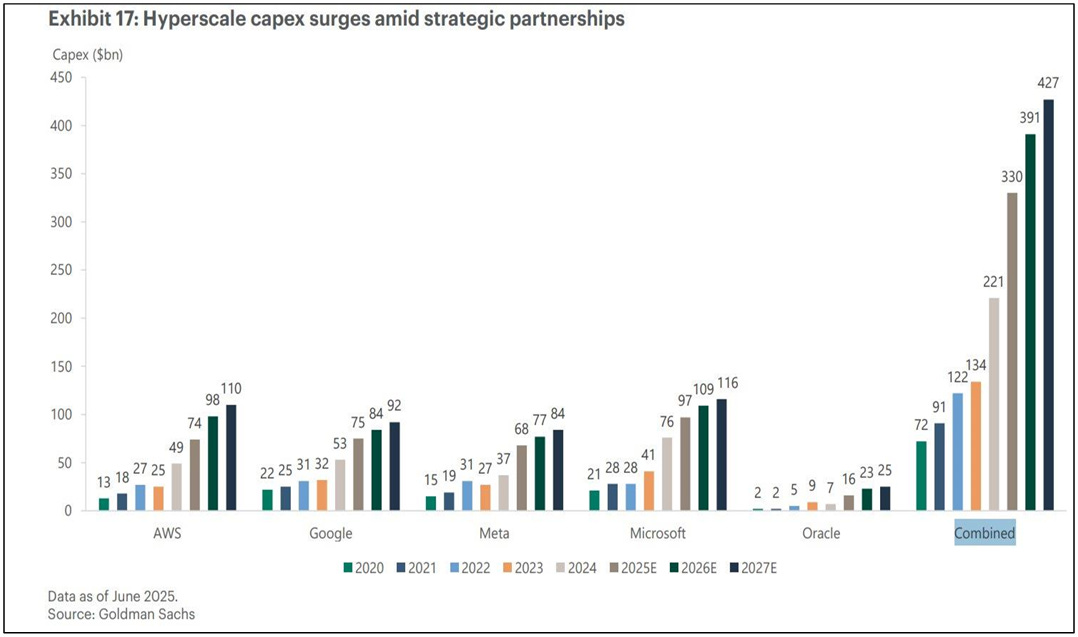

Let’s start with total datacenter spend for 2025. Insiders think it’s going to clock in at around $400 billion. If it misses that figure, it’s only because of bottlenecks that slow buildouts. Of course, it could also exceed that number, as those who are spending on these datacenters are beyond desperate to get them operational. For the sake of this piece, let’s use the $400 billion number, though it is likely a bit higher than where things may end up due to delays in construction.

What’s a datacenter made of? There are three main components; the building and land at roughly a quarter of the cost, all the power systems, wiring, cooling, racking, etc. at about 40% of the cost, and then the GPUs themselves at about 35% of the cost. I am sure I’m off by a few percent in these categories, but I’m relying on AI and we all know it’s still imperfect. I’m assuming that the building depreciates over 30 years, the chips are obsolete in 3 to 5 years, and then the other stuff lasts about 10 years on average. Call it a 10-year depreciation curve on average for an AI datacenter. Which leads you to the first shocking revelation; the AI datacenters to be built in 2025 will suffer $40 billion of annual depreciation, while generating somewhere between $15 and $20 billion of revenue. The depreciation is literally twice what the revenue is.

Now, here is where it gets complicated as there is no gross margin in the AI game. They’re literally giving away the technology and occasionally getting a nickel back for every dollar they give away. Calculated as a gross margin, it would be -1,900%. This is the nature of trying to drive adoption and get customers attached to a product. VC has a long history of funding this sort of thing, as long as the ROIC eventually flips positive. With nothing to go on, I’m going to take an optimistic guess here, and say that ultimately, the margins get to positive, and then gradually creep up towards 25%. Why 25%? I have no idea. It just sounds right because electricity is really expensive and you need a lot of expensive tech nerds to manage the equipment. Honestly, no one really knows where gross margins eventually land, so let’s just run with it, so that we can do some simple math. The question is, how much revenue do you need to cover the depreciation cost of the datacenter?

By my math, you need $160 billion of revenue at that 25% gross margin, which gives you $40 billion of gross margin against $40 billion of depreciation. Now, remember, revenue today is running at $15 to $20 billion. You need revenue to grow roughly ten-fold, just to cover the depreciation. Except, no one does anything to break even in business. For a new technology like this, with huge obsolescence risk, what unlevered ROIC would you demand? Would you want a 20% ROIC? That’s still dilutive to the ROIC for most of the largest capex spenders. Even at that dilutive ROIC, you’d need $480 billion of AI revenue to hit your target return.

Now, I think AI grows. I think the use-cases grow. I think the revenue grows. I think they eventually charge more for products that I didn’t even know could exist. However, $480 billion is a LOT of revenue for guys like me who don’t even pay a monthly fee today for the product. To put this into perspective, Netflix had $39 billion in revenue in 2024 on roughly 300 million subscribers, or less than 10% of the required revenue, yet having rather fully tapped out the TAM of users who will pay a subscription for a product like this. Microsoft Office 365 got to $ 95 billion in commercial and consumer spending in 2024, and then even Microsoft ran out of people to sell the product to. $480 billion is just an astronomical number.”

In an “if you build it, they will come” Field of Dreams-approach to the future, the so-called “Hyperscalers” are slated to spend over $1.1 trillion on capex for AI infrastructure projects through 2027. This will equate to more than 100% of their trailing 12-month operating cash flow. This compares to only $500 billion in total cloud revenue generated by the hyperscalers since the launch of Chat-GPT in late-2022. Moreover, Goldman Sachs estimates that only about 10-15% of cumulative cloud revenue generated by the hyperscalers or a total of $50-75 billion amounts to AI related revenue that is incremental to their installed cloud revenue base or about 6.5%. In short, if the hyperscalers go through with their planned capex spend, they are taking an enormous risk that revenue growth can/will keep up. Kuppy continues:

“Of course, corporations will adopt AI as they see productivity improvements. Governments have unlimited capital—they love overpaying for stuff. Maybe you can ultimately jam $480 billion of this stuff down their throats. The problem is that $480 billion in revenue isn’t for all of the world’s future AI needs, it’s the revenue simply needed to cover the 2025 capex spend. What if they spend twice as much in 2026?? What if you need almost $1 trillion in revenue to cover the 2026 vintage of spend?? At some point, you outrun even the government’s capacity to waste money (shocking)!

Simply put, at the current trajectory, we’re going to hit a wall, and soon. There just isn’t enough revenue and there never can be enough revenue. The world just doesn’t have the ability to pay for this much AI. It isn’t about making the product better or charging more for the product. There just isn’t enough revenue to cover the current capex spend.

Let’s go back in time, almost three decades back. It was the late 1990s and I sent my first email. It was amazing. I then used AOL Messenger to speak with someone on a different continent. Think about the late 1990s and how innovative this was. Back then, the local telephone company would charge you extra if you made a call outside of your zip code, which was basically 10 miles away. To call a different continent would cost almost a Dollar a minute, yet here I was, speaking with someone on the other side of the earth. Think about how groundbreaking this was. It was the AI of its day. No wonder we had a huge bubble in this stuff, it was obvious that the internet would change the world.

While we all remember Pets.Com and the hundreds of other Dot Com startups that flamed away, it was companies like Global Crossing, spending tens of billions on fiber, that facilitated all of this. That fiber, amazingly, is still in use. Global Crossing went bankrupt along the way, as did many of its peers. They overestimated what people would pay for this fiber, not that it would eventually be used or valuable.

Today, I watch in awe (stupefaction really), as companies continue to throw endless resources at AI, and I remember back to the Dot Com bubble and Global Crossing—fiber was the datacenter of that cycle, and Corning was the NVIDIA of its day (it lost 97% of its share price in the two years after it peaked).

I never thought we’d see another capex cycle like that one, a cycle that is almost completely devoid of revenue and profits. I really thought that the CEOs of today, educated with the lessons of the prior cycle, would never repeat the mistake of overbuilding at massive scale without revenue. Yet, here we are again. It’s bewildering.

There’s something else that this AI cycle reminds me of. Remember shale, where all the cash flow had to keep going into the ground, or oil production declined and the EBITDA covenants got tripped?? Now you have mega-cap tech stocks that are spending almost all of their cash flow on datacenters for fear of missing out. These asset-light businesses suddenly have the capital intensity of a shale company. Even worse, since losing the AI race is potentially existential; all future cashflow, for years into the future, may also have to be funneled into datacenters with fabulously negative returns on capital. However, lighting hundreds of billions on fire may seem preferable than losing out to a competitor, despite not even knowing what the prize ultimately is.

Carrying the thought process a step further; if there is no cash flow, and the returns on incremental invested capital are now deeply negative, why won’t these mega-cap tech stocks eventually be valued like a shale company at 3 times OCF? I know, it’s crazy to even contemplate given current valuations, but if you’re on a race to nowhere, and there’s no offramp, shareholders will eventually pull the plug. We saw something similar in shale. Even the MAG7 will not be immune. Eventually shareholders will hate the capital destruction—even if at first, they cheered it on out of ignorance.

As I see it, either the arms race continues, and the mega-cap tech names are forced to lever up to keep buying chips, after having outrun their own cash flows; or they give up on the arms race, writing off the past few years of capex. Then again, maybe they do the write-offs, but only after their share prices are impaired as investors pull the plug. Like many things in finance, it’s all pretty obvious where this will end up, it’s the timing that’s the hard part.

Then again, I’m just a boomer with some back-of-the-envelope math here. I don’t pretend to understand technology. However, I’m a guy who understands cash flow, and there is none. I don’t see how there can ever be any return on investment given the current math. Instead, I just see endless losses, and we’re far enough along in this S-Curve to think that we can at least start to model the returns—except they’re horribly negative. If the management teams at these mega-cap tech companies do not pull the plug on this adventure, eventually the shareholders will.”

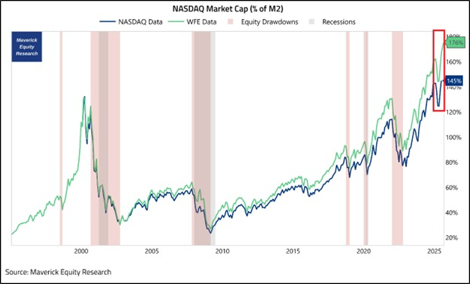

The AI Bubble’s advance has already more than tripled that of the Dot-Com Bubble. How much further can it go? Forgive our endless rant about valuations, but to put the above discussion in context, it is important to recognize that the market-cap of the Nasdaq 100 index (of which the Mag-7 represents 44%) relative to the U.S. M2 money supply just hit a record 176%, according to the World Federation of Exchanges (WFE). This means the market value of the Nasdaq 100 is nearly twice as large as the the total stock of liquid money in the economy. This valuation ratio has now exceeded the Dot-Com Bubble peak by about 45 percentage points. Never in the history of financial markets has the rise in stock prices exceeded the growth of the money supply by this magnitude. Unsinkable? Don’t bet on it!

Below we’ll illustrate how the weight of the evidence now favors a significant decline in growth in the back half of the year, while inflation pressures continue to remain sticky. We discuss how tariffs, if allowed to persist, act as a headwind to consumer spending, while lower rates reduce the income available to be spent and invested back into the economy. We also show how efforts to reduce the Federal deficit are withdrawing fiscal stimulus from the economy. In addition, we will examine a broad array of geopolitical events including President Trump’s attack on Fed, his attempt to end the war in Ukraine, and the implications of the recent Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit held in Tianjin last weekend. Finally, we present our comprehensive analysis of equity markets, real estate, commodities, currencies, crypto, and rates, then review our “Perfect Portfolio” tactical asset allocation strategy (+17.7% year-to-date through 8/31/25), which details how we believe investors should be positioned today in order to thrive during what promises to be a period of sustained volatility in the weeks and months immediately ahead.

Let’s begin…